For months, the U.S. government and financial institutions have been operating in crisis mode, frantically crafting emergency programs designed to forestall a systemic economic collapse.

The steps taken during these times have challenged longstanding assumptions about the operation of modern free-market capitalism and the role of the government in the economy. In the aftermath of the crisis and the inauguration of a new, more activist Democratic administration, U.S. economic thinking seems to be at a historic turning point.

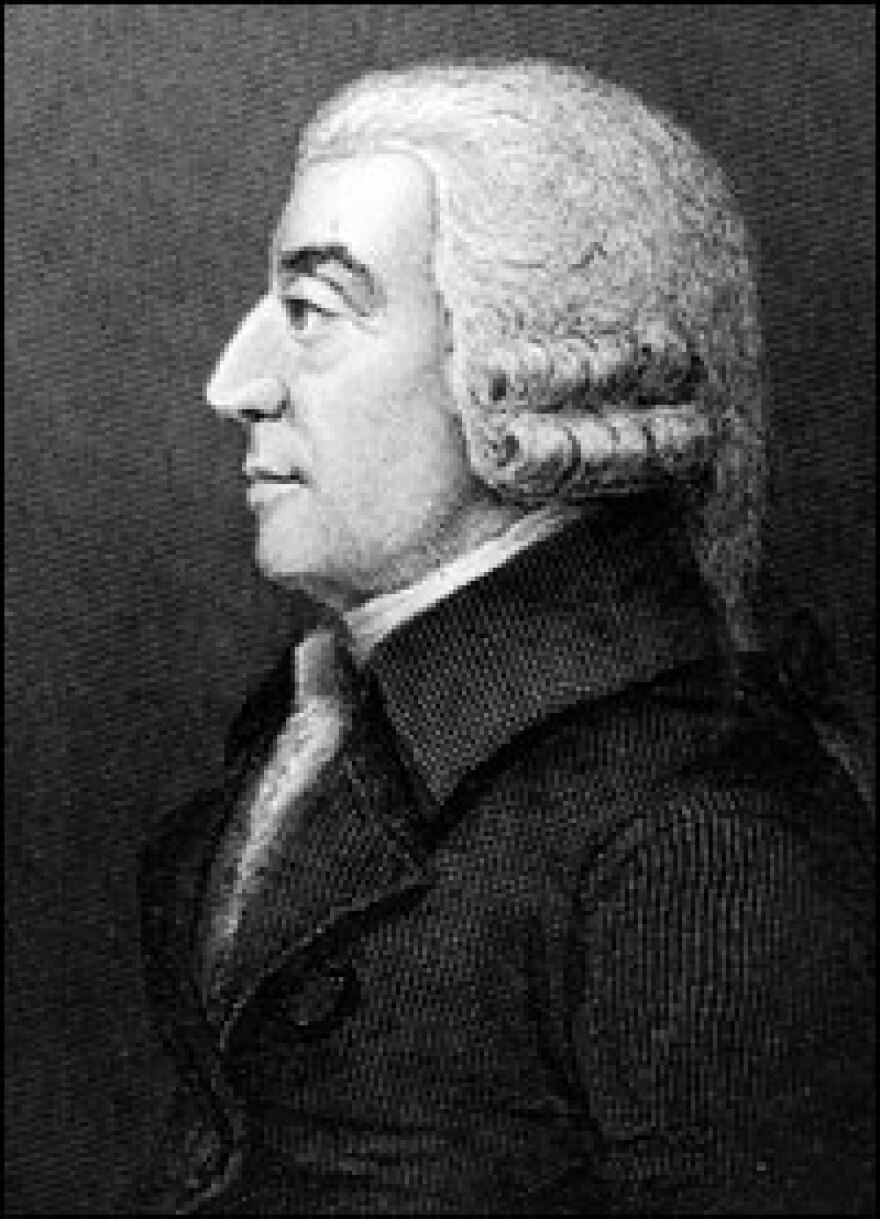

The idea of capitalism as an economic system was explained more than 200 years ago by the Scotsman Adam Smith. In his book The Wealth of Nations, Smith said a free market guides a society to efficiency by bringing buyers and sellers together and stimulating economies to produce more of what's needed and less of what's not.

In the United States, the best known apostle of free-market capitalism was the legendary economist Milton Friedman, who died in 2006. In 1980, Friedman made the case for Adam Smith's capitalism model in a 10-part television series called Free to Choose.

The 'Invisible Hand'

"[Smith's] key idea was that self-interest could produce an orderly society benefiting everybody," Friedman explained. "It was as though there were an invisible hand at work."

In theory, the "invisible hand" of the free market destroys companies that can't compete. But it lifts up companies with good ideas, ones that sell. The Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter called this "creative destruction."

Free-market true believers say governments generally should stand back and let this process run its course.

The pro-market, laissez-faire philosophy reached a heyday in the 1980s in Britain under Margaret Thatcher and in the United States under Ronald Reagan. In a 1986 message to American farmers, Reagan famously quipped, "I've always felt the nine most terrifying words in the English language are, 'I'm from the government and I'm here to help.' "

President Reagan supported the broad deregulation of the U.S. economy, in order to minimize the government role. In the years that followed, pro-market principles continued to guide U.S. economic policies.

But in 2008, the global economy nearly went into full meltdown. The Bush administration, at the urging of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, concluded it had no choice but to intervene in the marketplace, to save companies whose failures could have set off dangerous chain reactions: first, the mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and then the American Insurance Group (AIG), the largest insurance company in the world.

Adam Smith's Model Outmoded?

The free market had allowed such companies to make bad investments that put institutions around the world at great risk. Many economists, including some from Wall Street, said the lesson was that free-market ideology had been carried too far.

"We sort of morphed from Adam Smith's invisible hand, that markets move things in a very helpful direction, to some notion [that] free markets have an infallible hand," says Robert Barbera, chief economist at the Investment Technology Group (ITG).

The simple capitalism model that Smith described no longer seemed to fit the complicated, highly interconnected global economy of today. In his book The Cost of Capitalism: Understanding Market Mayhem and Stabilizing our Economic Future, Barbera says it's time to update our economic thinking. Schumpeter's idea that it's good for companies to fail and others to take their place usually makes sense, Barbera says, but not always.

"Wal-Mart appears. It's very innovative, and many, many small retailers over time are put out of business. That's the price of progress," Barbera acknowledges. "That's Schumpeter's 'creative destruction.' Conversely, when you're in a position when a great many financial institutions have lent the wrong way and there's this chance for a dominolike default, there's nothing creative about that destruction. You've got to prevent it. That's the cost of capitalism: Periodically you will have to come to the rescue of the financial system."

The Bush administration, generally conservative and pro-market, came to this very conclusion when it rescued AIG. Clearly, new ground had been broken in economic thinking.

Not Too Big To Fail

Not surprisingly, free-market purists have objected to these moves. They say the government should just let troubled companies go down, no matter how big they are.

"How, going forward, are we going to avoid [another] situation like this, unless we say, in a few cases, 'Look, that's it!' " argues Thomas Woods, a senior fellow at the libertarian Ludwig von Mises Institute in Auburn, Ala.

"I'm telling you that would have more of a salutary effect than all the regulatory tinkering put together," Woods says. "If these guys saw that, just like everybody else, if they don't produce, they fail. They're just like the guy who's a mechanic, the guy who's a plumber. They enjoy no special privileges."

Woods lays out his argument in his book, Meltdown: A Free-Market Look at Why the Stock Market Collapsed, the Economy Tanked, and Government Bailouts Will Make Things Worse.

A History Of Intervention

Actually, however, there's nothing new about American capitalism changing in response to developments in the economy. When the free-market system allowed monopolies to emerge in the 19th century, the Interstate Commerce Commission was created to control them. And the Great Depression, 70 years ago, brought another layer of government intervention in the U.S. economy.

The free-market champion Milton Friedman, in fact, said the U.S. government erred during the Depression by not intervening quickly enough. In one segment of his Free to Choose TV series, Friedman explained how the failure of one private New York bank in 1931 set in motion a whole series of bank failures around the country. It was, Friedman explained, an emergency situation that demanded an intervention by the Federal Reserve. But the Fed failed to act.

"The Federal Reserve system stood idly by when it had the power and the duty and the responsibility to provide the cash that would have enabled the banks to meet the insistent demands of their depositors without closing their doors," Friedman argued.

It is now widely accepted, even by most pro-market economists, that in a financial crisis, the government needs to intervene, even aggressively. What largely sets economic thinkers apart from each other is their view about what governments should do in addition to rescuing troubled banks.

"Most economists to the left of Friedman will say, 'Well, yes, this is one example where the government should intervene actively, but there are lots of others, too,' " says Brad DeLong, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

The Government's Expanding Reach

This is where the debate is now. The U.S. government, last fall under President Bush and then under President Obama, has gone well beyond rescuing banks. The practice of American capitalism has fundamentally changed.

"Remember those days in September when we woke up and found that the U.S. taxpayer now owned two large mortgage companies and an insurance company, AIG?" DeLong asks. "And now we're going for auto companies, and who knows what's going to go next? The U.S. government is taking over an awful lot of things and expanding its role in the economy quite strongly and quite aggressively."

Obama says he does not want the U.S. government's majority ownership of General Motors to mean Washington runs the company, but his administration is demanding more fuel-efficient vehicles. He says he's "a strong believer in the power of the free market," but that statement came even as he proposed regulatory reforms that would bring the biggest government intrusion into the private sector in more than 70 years. And then there are the administration's plans for energy and health care reform, both of which feature major new government roles.

Our free-market capitalist system will survive. But with each new economic crisis the guiding principles get revised.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.