How much lead does it take to ruin a brain? Not much, according to a new standard proposed for lead poisoning in children.

The amount of lead in a child's blood that determines dangerous lead exposure should be cut in half, from the current standard of 10 micrograms per deciliter of blood to 5 micrograms for ages 5 and below, a federal advisory committee said Wednesday.

That in itself would be a big step, and would double the number of young children in the United States officially considered to have lead poisoning to almost 500,000.

But the panel that recommended the changes went further, saying it should no longer be acceptable to wait until children have been harmed for something to be done. As the Advisory Committee on Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention's draft report put it: "Primary prevention is necessary because the effects of lead appear to be irreversible."

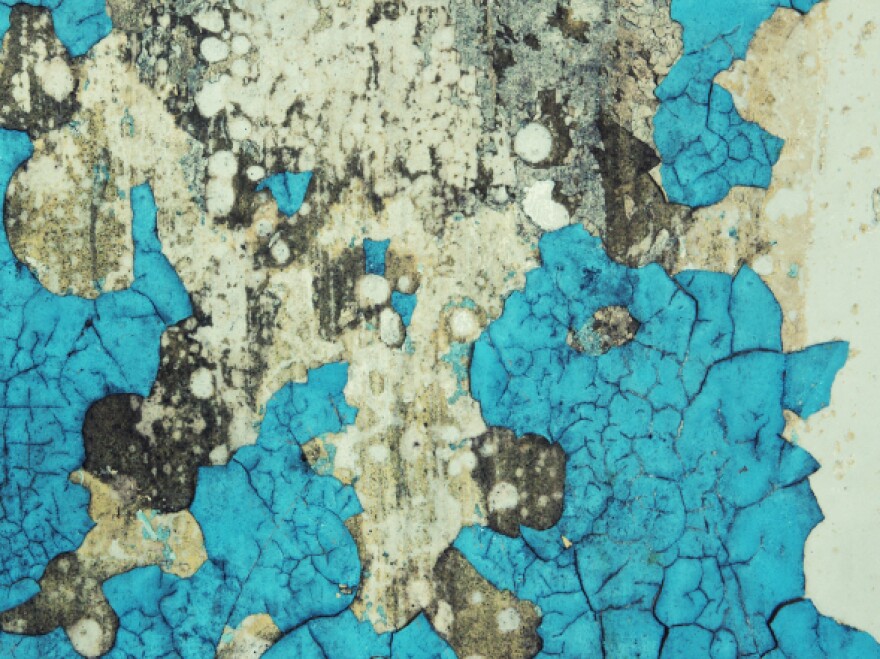

That means that no child should ever live in a building contaminated with lead paint, according to the panel's recommendations. "Children should not live in older housing with lead-based paint hazards," the committee's draft continues. "Screening children for elevated [blood lead levels] and dealing with their housing only when their [blood lead level] is already elevated should no longer be acceptable practice."

It's about time, says Jerome Paulson, a pediatrician at Childrens National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., who heads the Mid-Atlantic Center for Children's Health and the Environment. "We really need to screen houses, not kids."

Once a child has been exposed, Paulson says, "there's relatively little we can do. It may not prevent the decrease in IQ, the learning disabilities, the behavior problems." The present system, says Paulsen, uses "children as a means to identify substandard housing. To me, that's immoral."

Implementing a zero-tolerance approach would be a herculean task. About 24 million homes in the United States are contaminated with lead, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 4 million of those are homes with children.

Since 1988, when a federal law mandated efforts to remove lead from housing, the CDC and public health departments have labored to test children's blood and reduce exposure.

But still, an estimated 250,000 children have blood lead levels exceeding the current 10 microgram level. Many of those children haven't been diagnosed or treated.

When young children are exposed to lead, the toxic metal damages the brain and other organs. Children suffer reduced intelligence, ADHD and other behavior problems. Lead can also cause cardiovascular and immune system problems.

Lead paint in buildings built before 1978 is now the main source of lead contamination, but it can also come from paint on imported toys, jewelry, candy, and poorly glazed pottery.

Public health advocates have been pushing for this lower standard for 20 years, arguing that exposure to even tiny amounts of lead lowers intelligence and increases behavior problems, problems that can persist through life. And in 2004, the CDC started calling for removal of lead from all family housing.

It's been a tough sell. After lead was banned from gasoline, the number of children with lead above the current action level fell from 8.6 percent in 1988 to 1.4 percent in 2004, according to a 2009 study.

It looked like the problem was largely solved, except for a small number of unfortunate people, almost all poor, living in substandard housing that had yet to be cleaned up.

But that didn't end debate over how much of a toxic substance it takes to do harm, not just with lead but with thousands of man-made chemicals and naturally occurring substances.

In the past 10 years, a lot of work has gone into figuring out just how much lead it takes to damage a young child's brain. The answer is not very much. And though poor children are still disproportionately affected, children in all socioeconomic groups are at risk.

The committee's decision to lower the blood lead standard has to be approved by the CDC, which isn't necessarily a sure thing. "We really have to wait and see how the CDC is going to react," says Carla Campbell, a pediatrician at Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia, who headed an earlier lead advisory panel. "It's a little early to know whether there's going to be a sea change."

And decisions to ramp up prevention efforts will no doubt take much, much longer.

Parents wondering what they can do to protect their children can check the CDC's Healthy Homes website for links to state and local programs on lead testing and remediation. The Consumer Product Safety Commission also has information on safely removing lead paint.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.