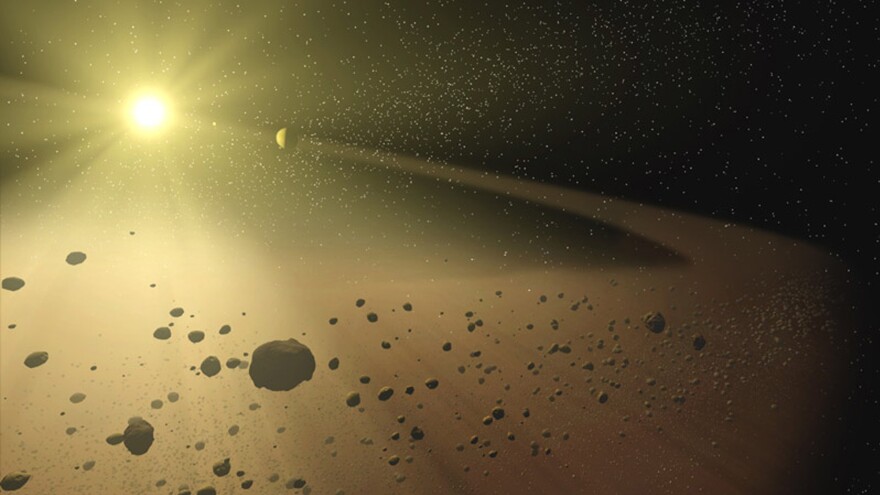

The asteroid belt, a ring of rubble between Mars and Jupiter, has sometimes been written off as discarded leftovers from the solar system's start. But new research published in the journal Nature shows that the belt actually formed during an unruly later era, when planets themselves were on the move.

For decades, astronomers have thought the belt formed from the same cloud of dust and rock that made our planets. That theory was based on observations of just a few asteroids in the 1980s. Astronomers have seen a lot more asteroids since then.

"There have been some really large surveys over the past decade or so that have expanded our understanding from a couple thousand asteroids to hundreds of thousands of asteroids," says Francesca DeMeo, an astronomer at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

When DeMeo and her co-author, Benoit Carry of the Paris Observatory, looked at all of these new asteroids, they found something surprising. Many of the rocks looked like they'd come from somewhere outside the asteroid belt.

"What we see today in the asteroid belt is sort of this melting pot of asteroids that formed in all different locations throughout the solar system," DeMeo says.

The duo's analysis has upended old views of the belt. "This really is beautiful work," says Kevin Walsh, a theorist with the Southwest Research Institute. "They did an awesome job."

But if asteroids came from all over, how did the belt come together?

The answer, says Walsh, might be planets. New theories suggest that early on, our planets weren't in pretty orbits. At the beginning of the solar system, 4.5 billion years ago, the nebula of dust and rock that formed the planets also pulled them around with gravity. Later on, Walsh says, the planets themselves might have sent each other spinning off in new directions.

Whenever they left their tidy orbits, the planets flew through a cloud of asteroids. And as they moved, they shook up these rocks, like flakes in a snow globe. According to this view, many asteroids "were launched into the asteroid belt and implanted there," Walsh says.

Richard Binzel, a planetary scientist at MIT, says that according to this view, the planets are much more active than earlier models suggested.

"They're scattering the asteroids, they're flinging them off up, down, sideways. Some [asteroids] leave the solar system; some go crashing into the sun," he says.

These were some pretty big planetary swerves. Mars might have veered very near Earth. And the solar system's largest planet, Jupiter, may have swooped to near where Mars is today.

"Jupiter sort of ruled the roost and was sort of the big bully of the neighborhood," Binzel says. "And as Jupiter migrated, it would push and pull and tug everything else along with it."

In fact, Jupiter may have had a big impact — literally — here on Earth. Jupiter's swing into the inner solar system flung a lot of asteroids toward us. Our planet got battered. Francesca DeMeo says the effect of this bombardment could have been profound.

"It could have actually caused some of the asteroids to hit Earth but deliver water at the same time, so that could be the reason that we have oceans on Earth and the Earth can support life," she says. "But it also can cause destructions, where if you have too many asteroids raining when life has already formed, then it's a destructive force."

Questions like whether asteroids brought life to Earth, or extinguished it, can't yet be answered. But this new asteroid survey seems to confirm that giving birth to a solar system is more chaotic and dangerous than anyone thought.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.