Before writing his new book, The War Lovers, Evan Thomas, the assistant managing editor of Newsweek magazine, spent three years researching an event a century removed from his day job: the 1898 Spanish-American War. But he did so, he says, because of similarities he perceived between the way America entered that conflict and the way it approached the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Thomas says part of what drove him to consider America's war with Spain was his own feeling that "it was a good idea to invade Iraq." Later, second-guessing that conviction, he looked to history for parallels.

"Spain owned Cuba at the time, and the Cubans had been off-and-on rebelling for years, and we just finally decided to help them out," Thomas tells NPR's Steve Inskeep. "So there was a legitimate reason for going to war. We did liberate Cuba. But I don't think that was the main reason for doing it."

In The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst and the Rush to Empire, 1898, Thomas explores the reasons that drove a few influential Americans to zealously support the cause of war.

There was a desperate appetite for war among some Americans in the 1890s, Thomas says. Among them, the three men mentioned in his subtitle: newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who stood to benefit from increased sales for papers that shouted war headlines; Massachusetts politician Henry Cabot Lodge, a leading imperialist who, Thomas writes, was greatly influenced as a child by the heroes of the Civil War; and future President Theodore Roosevelt, whose attraction to war was both political and deeply personal.

Thomas says Roosevelt wasn't particular about who the opponent was. He even wrote letters advocating for war with Germany, or with England, for the purposes of liberating Canada.

"He was ready, really, for any war, because he felt that Americans were growing soft," Thomas says. " 'Overcivilized' was the word that he used. And he felt that we needed to recapture what he called 'the wolf rising in the heart,' a kind of animal spirit that all great nations have."

Roosevelt had personal motivation, as well.

"He had this constant need, all through his life, to prove himself physically," Thomas says. "He was a weakly, sick kid with asthma, and he hiked, and then he became a great hunter. And he would rate animals based on how dangerous they were. And of course the most dangerous game is man, and he wanted to fight in a war to test his courage by hunting men."

Not everyone was so enthusiastic. President William McKinley wanted to avoid war. He'd fought in the Civil War and had "seen the dead stacked up at Antietam," Thomas says. But the efforts of men like Hearst, Lodge and Roosevelt helped to whip up popular fervor.

"At Congress, they were basically having pep rallies," Thomas says. "The country just wanted a war."

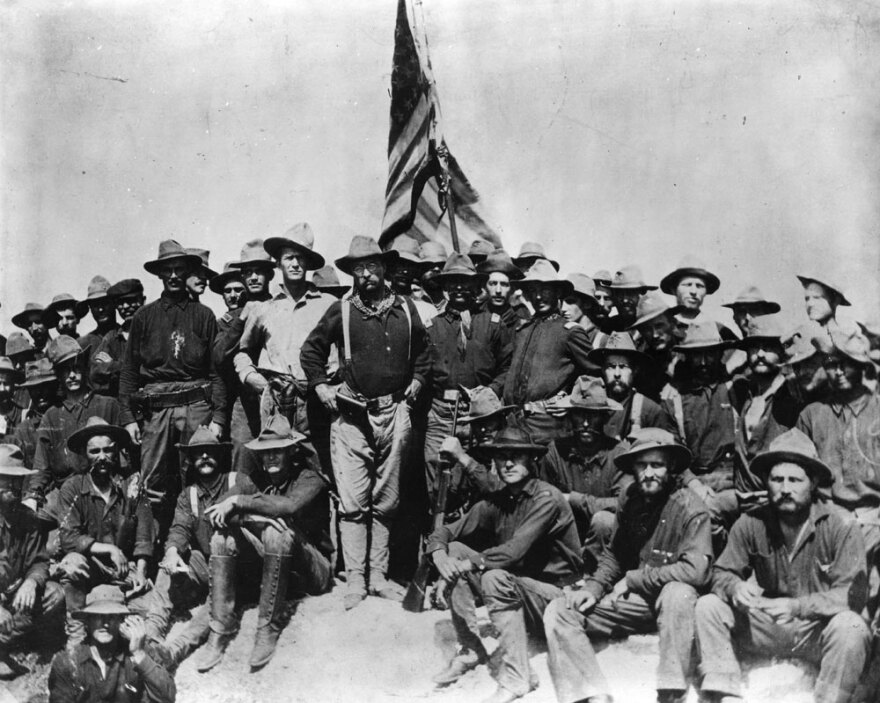

For Roosevelt, the war was an astonishing success. He quit his desk job as assistant secretary of the Navy, enlisted in the cavalry and went to Cuba, where he led the Rough Riders in the Battle of San Juan Hill. When he returned, he was elected governor of New York. Two years later, he was elected vice president. When McKinley was assassinated in 1901, he became the youngest president ever.

But not all the actors on this stage were as well-remembered. As Thomas puts it, Thomas Brackett Reed is a "pretty obscure figure" today. But at the time, he was one of the most powerful and outspoken opponents of the war. The Maine congressman and speaker of the House managed, for a time, to keep the House from voting on the war, but in the end, he couldn't hold out.

"It broke his heart. At the end, he didn't even show up to vote," Thomas says. Reed's career fell as quickly as Roosevelt's rose: "He couldn't understand what this war fever was about. I think he had common sense. But he was the loser. As society got swept up, he was the guy who lost out." After America went to war, Reed resigned from Congress. He died in 1902.

Thomas says the United States' "imperialist urge" waned after the Spanish-American war. He acknowledges that as he did research, he learned lessons about America's current wars that he "should have known from the beginning."

"We talked about weapons of mass destruction and so forth, but I think that the main reason the Bush administration went to war in Iraq was because we wanted to teach the world a lesson after 9/11," Thomas says. "We wanted to -- to put it crudely -- to kick some ass."

"We got sucked into something that actually has turned out OK. We did achieve some war aims, but we did it at great cost, and clearly we didn't know what we were getting into."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.