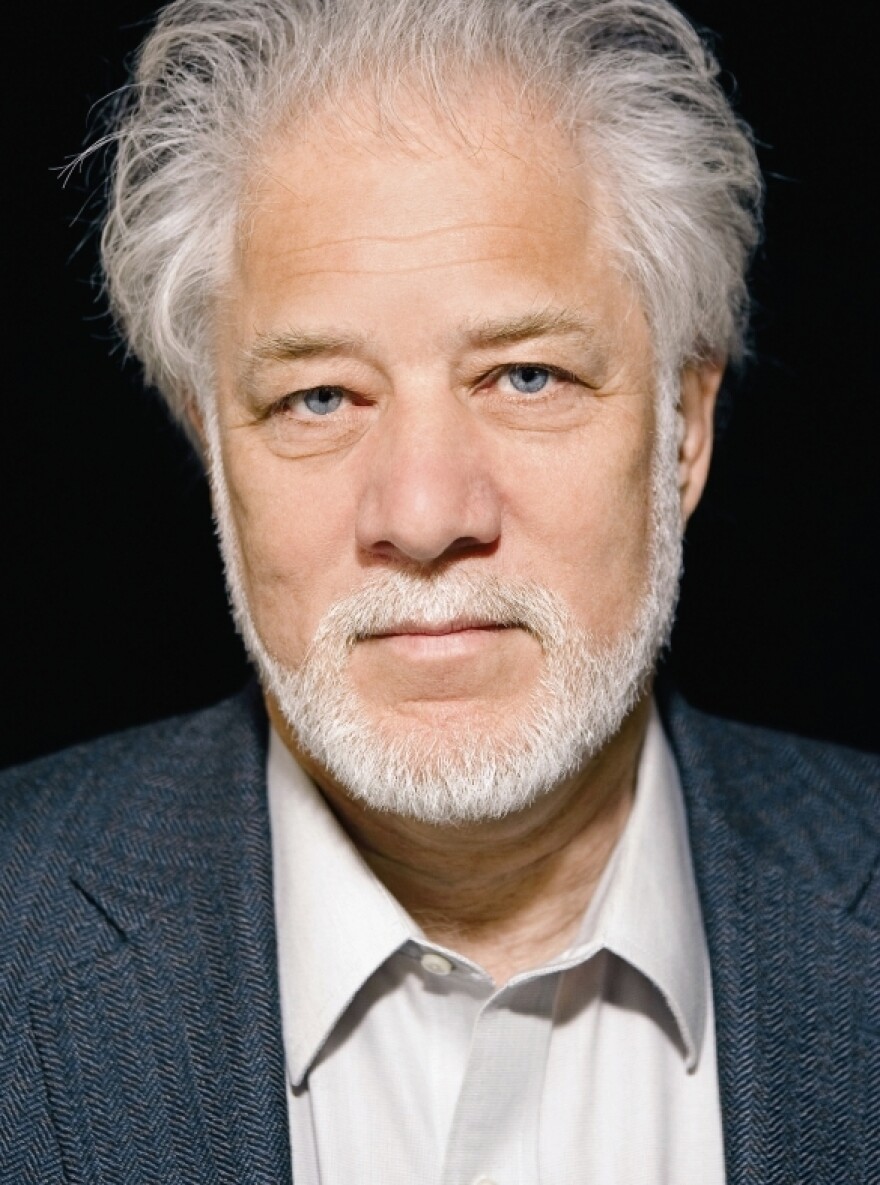

In writer Michael Ondaatje's mind, the "cat's table" is where the undesirables sit in a boat's dining room. It's for the hecklers, the lowly ones and the ones farthest away from power. And it's also where you'll find the narrator of Ondaatje's new novel, Michael, an 11-year-old who's on a 21-day voyage from Sri Lanka to London all on his own.

He and his companions — two other boys who are travelling alone — live by only one rule: to every day do at least one thing that is forbidden.

Ondaatje — who also wrote The English Patient — tells their story in The Cat's Table, a book set in the 1950s that is part boyhood romp, part crime novel and part nostalgic reflection as an adult Michael looks back on how the trip shaped his life.

Ondaatje tells NPR's Michele Norris that the idea for his new book came from personal experience: he went on a similar journey when he was a young boy. He says that looking back, his own voyage seems very strange to him.

"You wouldn't put your kid on a bus to go across America, let alone on a ship for 21 days," he says.

Despite the book's resemblance to reality, the author says that his goal in writing The Cat's Table wasn't to rediscover the boy he was; it was to write a fictional version of something that had been forgotten.

"About halfway through, I suddenly named the boy, or the narrator, Michael," after himself, Ondaatje says. "It had an odd effect on me in that calling him Michael separated him from me so that he began to change. He was a very different kind of person to what I am."

Capturing The 'Feral Quality' Of Childhood

On the ship, the boys occupy a world that is shaped by their adventures. They begin their day before the sun rises, plunging into the gold-painted first-class pool and raiding the sundeck's breakfast table before other passengers are awake.

Ondaatje, who is in his 60s, says writing about the lives of rambunctious children wasn't too much of a stretch for him.

"Something I realized much later on is that some of the most anarchic and perhaps accurate books about childhood — that catches that feral quality — are often written by older people," he says. "We think about a film like Fanny and Alexander by Ingmar Bergman; it's a wonderful film about childhood and he was quite an old man when he wrote it. There's something about looking back that allows you a freedom to invent bad behavior."

Looking back can also provide a certain amount of perspective. It isn't until he's older that the fictional Michael begins to recognize the longing that haunted him as a child; he's flooded with memories and the sense that he's missing something, even though he's clearly surrounded by people who care about him.

Michael Ondaatje has also the author of The English Patient, Running in the Family and In the Skin of a Lion.

Or, for that matter, if she will recognize him.

Crafting A Novel By Hand

Part of the book's brilliance is the way Ondaatje presents his characters; it's almost like flipping through the pages of a scrapbook of Michael's memories, with characters moving from the background to the foreground of the story, and back again.

"I always have loved that element of having characters in a novel who disappear and then come back 50 pages later," Ondaatje says. "This is what happens in our lives. We lose contact with people, and then they come back, and they are altered and sometimes we don't know how they're altered."

And the constellation of characters Ondaatje invents is impressive. It seems like the only way to keep them all straight would be to plan them all out before you even started writing — but that's not how Ondaatje works.

"They appeared as I was telling the story," he says. "One of the things I do with my books is I write them and improvise when I'm actually writing that first draft and discovering what the plot is. But later on, I spend a lot of time rewriting, reshaping the book and underlining that architecture."

A lot of that rewriting and reshaping — the first four or five drafts, to be exact — takes place in hand-written manuscripts that lend a chaotic air to Ondaatje's office.

"It's an outrageously untidy office. No one can go there because it's so bad," he says. "The table is so full of stuff I haven't done, which I ought to have done."

Still, the office provides a small space for Ondaatje to spin his tales from. You can either view it as clutter, or as a small sign of brilliance.

"I think I might have seen a sticker in a car which said, 'A clean car is a sign of a sick mind.'" he says. "I'm really healthy if that's the case."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.