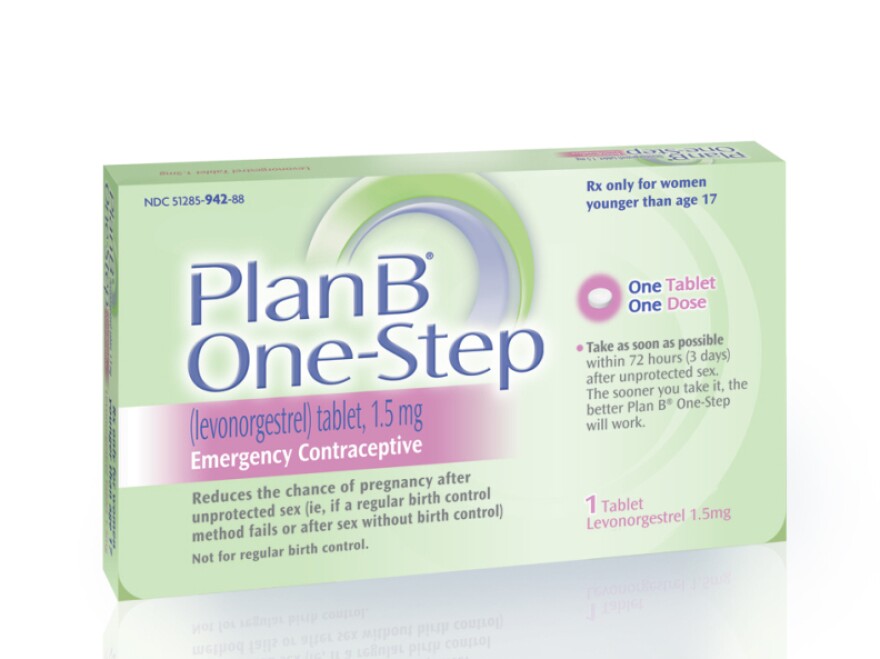

Critics cried foul when Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius overruled the Food and Drug Administration earlier this month, saying that teenage girls can't buy the emergency contraceptive plan B without a prescription. Their complaint: That the move went against the Obama administration's stated goal of protecting science from the taint of politics.

Despite the controversy, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy is continuing to push ahead with its nearly three-year-long effort to have all government agencies put new "scientific integrity" rules in place.

The Department of Health and Human Services is one of 13 agencies that submitted near-final draft policies to meet a Dec.r 17 deadline, according to a new blog post by John Holdren, Obama's top science advisor.

In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was to submit its latest draft to OSTP this week, and five other agencies already have final policies in place.

The goal of all this work is to make it less likely that scientific data is altered or suppressed, so that decision makers and the public have access to the most accurate and relevant information.

But, as Holdren notes in his blog post: "That does not mean that 'science trumps all' in the policy-making process." Economic and social realities also factor in, he said.

President Obama pledged in his inaugural address to "restore science to its rightful place" in federal decision-making, but the process of creating rules to protect science and scientists has been slow and less than transparent, according to watchdog groups that have been closely monitoring the effort.

One of the groups following the issue, the Union of Concerned Scientists, noted that of the 19 draft and final policies submitted to OSTP, only six have been made public.The departments of Interior, Agriculture, and Education, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and NASA have released their final policies, while EPA and the National Science Foundation have put out drafts so the public could comment.

"To protect and enhance their own credibility, the remaining agencies and departments should make draft or final policies immediately available and invite the public to help them improve their policies," said Francesca Grifo, director of the Union of Concerned Scientists' Scientific Integrity Program, in a written statement. "They should also disclose plans to meaningfully implement their policies by the end of the president's first term."

NPR recently used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain the final policy that the Office of the Director of National Intelligence provided to OSTP, which has not been made public. That policy encourages researchers to seek independent peer review from within and outside government, but doesn't give scientists a system to protest manipulation or suppression of their work.

In an email, policy analyst Gavin Baker with OMB Watch, a nonprofit that promotes government accountability, wrote that the four-page document struck him as helpful "in expressing some common principles about how to handle science in environments where many activities are classified. But these are modest principles that don't do much to prevent the political manipulation of science or to protect the free flow of scientific information."

Baker noted that several intelligence community agencies—such as the Department of Justice, Department of State, and Department of Defense—have submitted draft policies to OSTP and that he would only consider the intelligence community's final principles adequate if each agency had a strong and enforceable scientific integrity policy of its own.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.