The history of science is not limited to scientists in white coats working quietly with beakers and burners. Sometimes, in the name of knowledge, things can get downright weird.

In his new book, "Electrified Sheep," Alex Boese explores the unexpected side of science, filled with bizarre experiments and intrepid scientists.

Certain experiments served a purpose, like the zapping of animals, which helped scientists learn to harness the power of electricity.

Other experiments seem spectacularly useless, like the professor in 1933 who had a black widow spider bite him, confirming what scientists already knew — black widow spider venom really hurts.

"When we think of science, often we think of it as being very rational," Boese tells weekends on All Things Considered host Guy Raz, "(but) often scientists are blundering around in the dark ... So often, maybe out of desperation, they resort to doing these extreme things that really look kind of crazy."

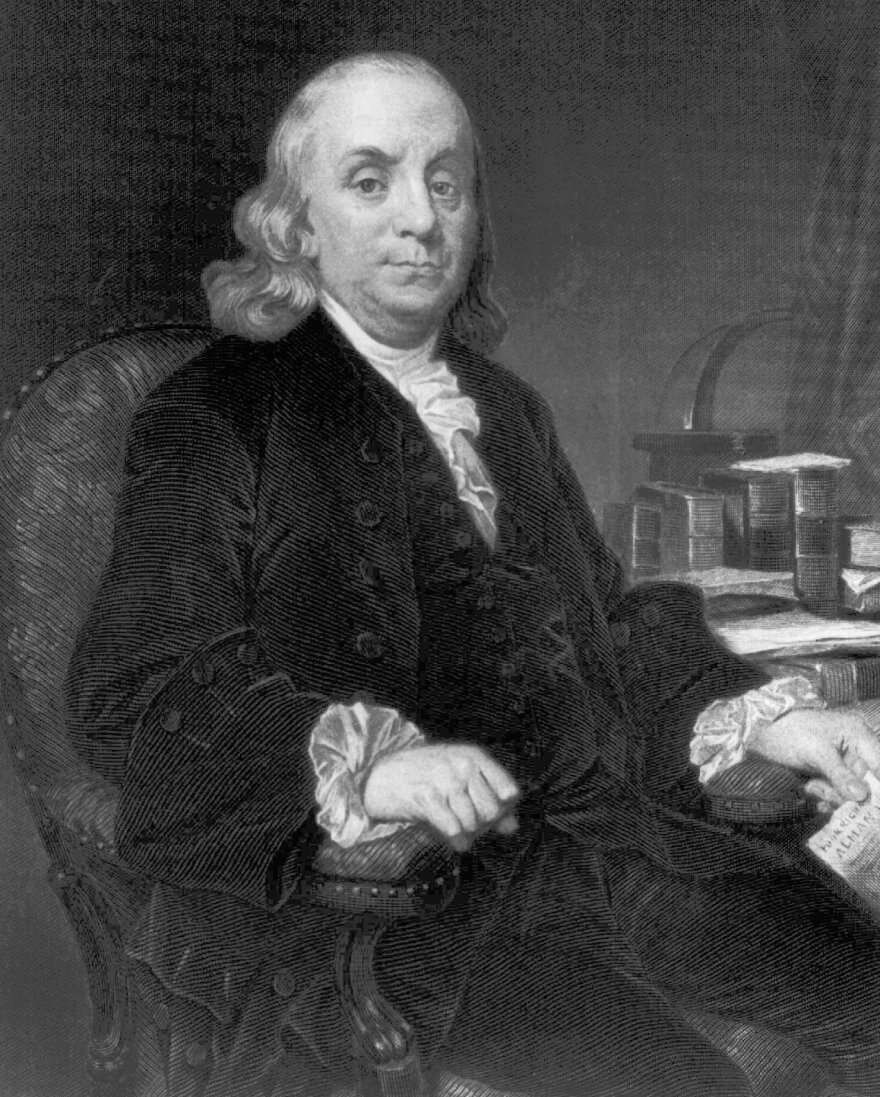

It might have looked crazy, but there was a scientific reason Benjamin Franklin had his mouth pressed against a hen's beak.

In the 18th century, when scientists first began to understand the power of electricity, they had no way to measure electrical force. There were, after all, no hardware stores selling voltmeters. But there were birds.

"So what they did," Boese tells Raz, "is they would zap these poor birds and see what effect it had on the birds. They could say, well you know, this amount of power was enough to kill a sparrow but it wasn't enough to kill a hen or a turkey ... And Ben Franklin was involved in research like this."

Interview Highlights

On Benjamin Franklin's bird encounter

"He was zapping away hens and turkeys. And one poor hen, he got the idea, 'Well, I just zapped it and it's here unconscious on the floor, let me try to give it mouth-to-beak resuscitation and see if it comes back to life.' And sure enough it did. So Ben Franklin has a kind of odd honor of being the first person to use artificial respiration to revive an electric shock victim."

On Evan O'Neill Kane's self-appendectomy

"Evan O'Neill Kane was a very prominent surgeon. And he found that his own appendix was inflamed; it needed to be removed ... (he) suddenly sat up in the operating room and said, 'Hang on everybody — stop — I'm going to do it myself' ... And he injected some cocaine into the lining of his stomach muscles and began to slice away. And the experiment — well, the operation — was successful, except for at one point all his guts popped out of his stomach. But he said he just composed himself and stuffed them all back in."

On Allan Walker Blair's spider bite

"He was under no illusions that the black widow spider venom is the deadliest, or at least the most painful, venom that you can possibly be stung with ... He left the fangs of the spider in his hand for 10 seconds. Sure enough, you know, three days of nightmarish pain in a hospital. The doctor who attended him said he had never seen that level of pain manifested in any patient for any reason whatsoever ... You have to wonder what was the point of this, since doctors already knew what the black widow venom did to people."

On whether these experiments benefited science:

"Absolutely, because if you think about it, science at its core nature is somewhat about doing things that normal people would think are crazy. For instance, the first people back in the 15th century who started doing human anatomy and cutting up bodies, at the time people though this was absolutely, not only insane, but wicked and sacrilegious. And yet they kind of went ahead and did it anyway ... So there's this kind of tension in science that yes, you have to kind of be willing to do what others are not willing to do. And if you don't do that, then science can't advance."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.