When Voyager I and II left Earth, Jimmy Carter was president, platform shoes were all the rage and moviegoers were still discovering a summer blockbuster called Star Wars.

Some 35 years later, the spacecraft have traveled farther than anything ever built by humans. Now there is evidence one of the plucky probes may soon cross the undulating boundary between the absolute edge of our solar system and the terra incognita of interstellar space.

"It's not that clear because there's no signpost telling you that you're now leaving the solar system, but the evidence is mounting that we're getting really close," says Arik Posner, a Voyager program scientist at NASA's headquarters in Washington, D.C.

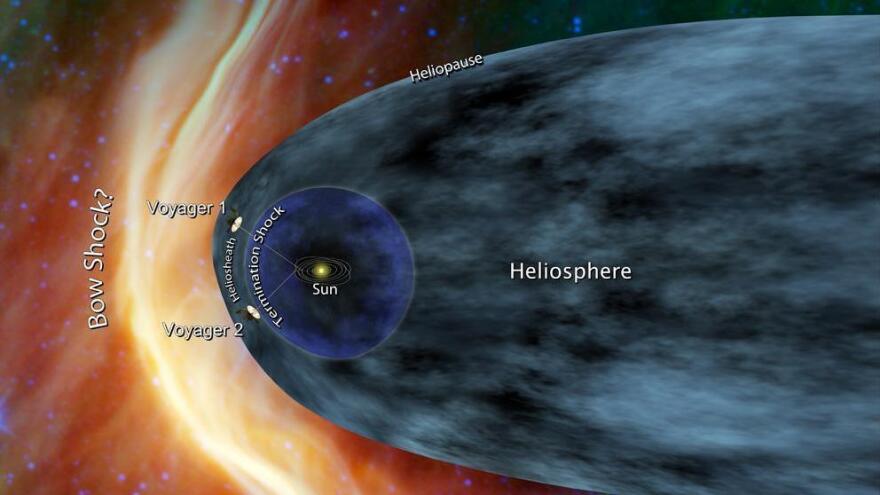

That boundary is a mysterious place called the heliopause, where scientists believe the solar wind — a stream of charged particles spewed out by the sun — fizzles out completely. Call it the cosmic doldrums, or perhaps even the heavenly horse latitudes. There are tantalizing signs that Voyager I, now some 11 billion miles from home, is nearly there. (Voyager II, which launched first, is about 2 billion miles behind its twin.)

Analyzing the heliopause and what lies just beyond is expected to be the Voyagers' last feat before they go black.

Like Columbus Crossing The Atlantic

For Posner, who is crunching data from a spacecraft that left Earth when he was still in grade school, the notion of humans leaving the solar system for the first time is extraordinary.

"Humanity eventually leaves the material that is constantly being expelled by the sun. I would compare it to the crossing of the Atlantic by Columbus," he says.

After launch in 1977, the Voyagers sent back the first close-up pictures of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and they have managed to keep working well beyond their shelf life. No one expected them to get this far, Posner says.

"But now that they've made it, we are extremely excited to find out what's out there," he says.

The program might never have happened had it not been for two employees working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the 1960s. The first was a UCLA graduate student named Michael Minovitz, who discovered that planetary gravity could be used to slingshot a spacecraft into deep space — something that had seemed hopeless using conventional rockets of the day. The second was Gary Flandro, who realized that a rare time window was about to open that would make it possible to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune in a single mission.

"We're talking about the 1960s, when we had pretty weak rockets," says Stephen J. Pyne, author of Voyager: Exploration, Space, and the Third Great Age of Discovery. "The only way to get to the outer planets was to have some sort of boost."

The 'Grand Tour'

A mission to embark on this "Grand Tour" had to be launched between 1976 and 1979. The next opportunity wouldn't come around for another 175 years.

"You're either going to do it now or your great-grandchildren are going to do it," says Pyne, who is also a life sciences professor at Arizona State University.

The Grand Tour, though ultimately scaled back, fundamentally changed our view of the outer solar system. Pyne recalls taking an undergraduate astronomy course in 1970: "I think there were about two pages in the standard astronomy book on the outer planets. That was it. They had some murky black and white photos and a brief description of the orbital mechanics. There was just nothing. Nobody knew anything."

By the time Voyager I reached the Jupiter system — including its four large inner moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — in April 1978, enough data were streaming in to fill volumes of future astronomy texts, says Fran Bagenal, a professor of astrophysical and planetary sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

"It wasn't until we got up close and saw the volcanoes on Io, the geysers spewing out sulfur dioxide, all the geology on Ganymede and the impact craters on Callisto that we really realized that these moons were totally different worlds orbiting these fabulous gas giants that had clouds and weather," says Bagenal, who worked on Voyager as well as later planetary missions.

"There was so much that we saw for the first time with the Voyager spacecraft," she says.

Postcards From Space

Voyager I also snapped a few images of its home planet as it hurtled toward deep space — the first vehicle to take a full-frame shot of the Earth and moon together. At the urging of famed astronomer Carl Sagan, it also took a picture that came to be known as the "pale blue dot."

While some of the Voyagers' instruments are dead, their radioactive batteries still have some life left in them. At some point in the next 10 to 15 years, presumably well after both probes have crossed into interstellar space, they will go out not with a bang, but a whimper.

Pyne, for one, hopes the Voyagers will take one last picture before that happens — an image that shows a faint sun and might become as iconic as the pale blue dot.

"I don't know if there's enough power, but I sort of hope they might have enough for one of them to turn around and take a snapshot before it goes," Pyne says.

"Sort of a final postcard mailed to Earth: 'Here we are, wish you well.' "

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.