In the 19th century, the Bowery Boys were a street gang that ruled that small section of Manhattan. In the 21st century, the Bowery Boys are two best friends — Tom Meyers and Greg Young — who record a do-it-yourself podcast with the same name.

Meyers and Young love to perform almost as much as they love New York City, and their show traces the unofficial history of the place. They record a few blocks from — you guessed it — the Bowery district.

Podcasts have been around for less than a decade, but in that short time, homemade shows have exploded. To date, "The Bowery Boys" has had more than 5 million downloads.

One episode is about Tin Pan Alley, in the Flower District, where 19th century composers churned out sheet music to distribute across the country.

"Charles Harris wrote a song called 'After the Ball' in 1892," Young says in that show. "He was lucky enough to get a vaudevillian star by the name of May Erwin to perform the song in her show, and it would sell up to 10 million copies. I mean, could you imagine, like, a Lady Gaga song rolling out over six years? Rolling out throughout the country?"

The Bowery Boys' audience doesn't quite rival Lady Gaga's, but 20,000 listeners isn't too shabby. Still, Meyers and Young are the first to admit that they are not professionals.

"We bought Podcasting for Dummies," says Meyers, "partially to figure out what a podcast was, and also how to record these things."

The pair doesn't use fancy equipment, either.

"I think that for the first episode, we recorded with a spare karaoke microphone that we had in the closet for ... other occasions," recalls Meyers, laughing.

In each episode, the two friends tell little-known stories about the history of their adopted city — Meyers grew up in Ohio and Young in Missouri, but they're more than qualified to talk Big Apple — like why a trip up or down Manhattan is quick and easy, but traveling a few blocks east or west takes much longer.

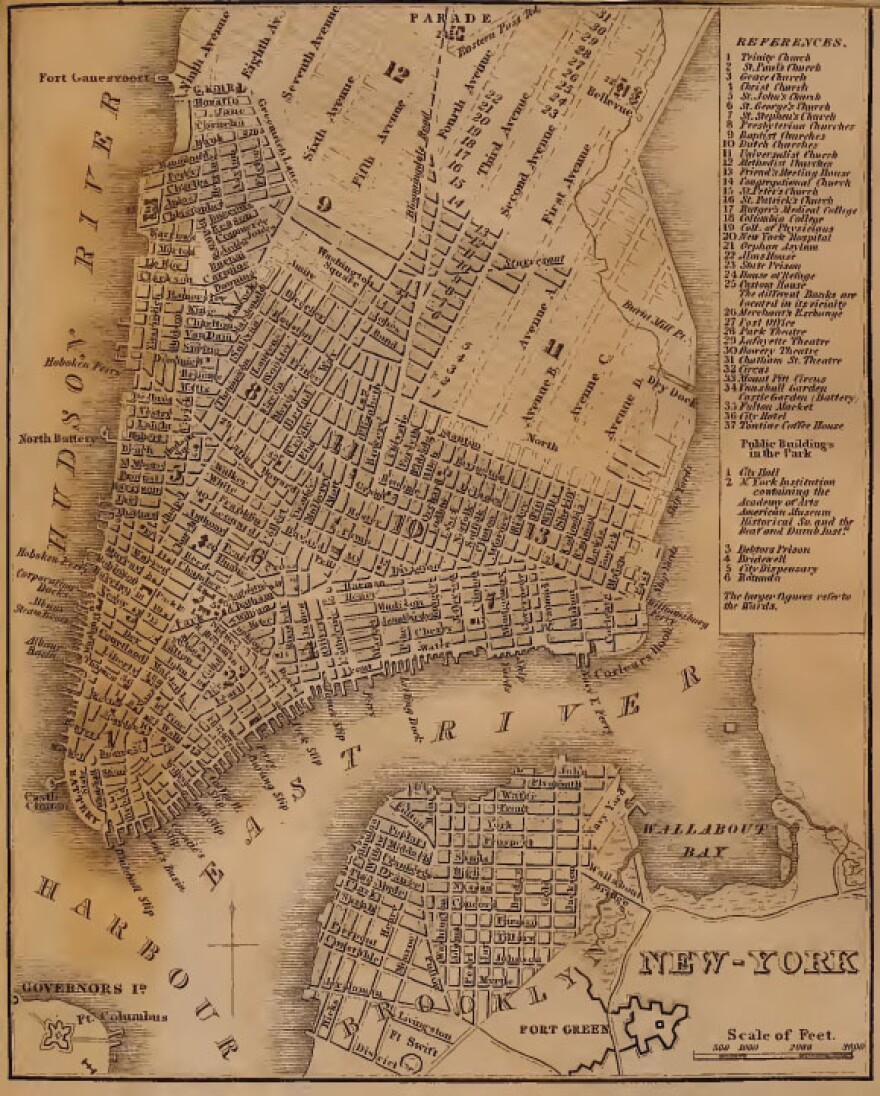

"That's because of decisions made 200 years ago by the Commissioners' Plan, through the use of a grid," Young explains in an episode called The Manhattan Grid Plan. "That is something that every New Yorker lives with every day."

Meyers and Young have touched on New York's iconic landmarks, like Times Square. But the Bowery Boys don't stop with the familiar.

In another episode, they take listeners to a 1960s theme park in the Bronx called Freedomland USA.

"It was shaped like the U.S.," Young explains in the episode, "and you went into each area, and there were themed rides and everything."

"What's happening over there in Chicago? Fire! Look at that!" says a voice in an old advertisement. "It's the Chicago Fire of 1871. Here at Freedomland, they have the Chicago Fire every half-hour, every day."

The quirky amusement park closed after only four years. Young says he likes an element of randomness to help choose episodes. And it works.

"I got responses [from] people who said, 'When I was a kid, my parents took me to Freedomland. And I thought I had made it up,' " he says.

The Bowery Boys pack an incredible amount of history into each episode — not so easy for two guys with day jobs. (Young works in music licensing for Sony, and Meyers runs his own online travel business.)

"I don't read anything that's not related to New York City history," says Meyers, "which is a little bit sad, because I'd love to read a novel that wasn't — I'd love to read a novel. But at the same time, I can't get enough."

The Bowery Boys' podcast now includes a blog that gets about 100,000 hits each month. And Meyers and Young have become unofficial ambassadors of New York City history; they've appeared on local television and done events with the city's Municipal Arts Society.

"We don't pretend to have doctorates in the subject," says Meyers. "[But] I feel like we are getting our own degree in this. ... We are home-schooled historians."

Home-schooled, maybe. But five years and just shy of 150 episodes later — when it comes to New York City, they're schooling us.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.