Remember that wacky glue commercial from the 1980s? "Krazy Glue, you crazy rat," the narrator says. "Strong enough to hold this man suspended in mid-air." He promises the stuff can bond almost anything: a plastic knob, a plastic plug, a rubber boot, a door knob, and even a flashlight case.

Heck, a version of the everlasting adhesive is even approved by the Food and Drug Administration to seal skin wounds.

But superglue can't fix a broken heart — or even a torn artery. Yet.

Now a team of doctors and engineers at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston are getting close to changing that. Their unlikely inspiration is a 3-inch worm that lives off the coast of California.

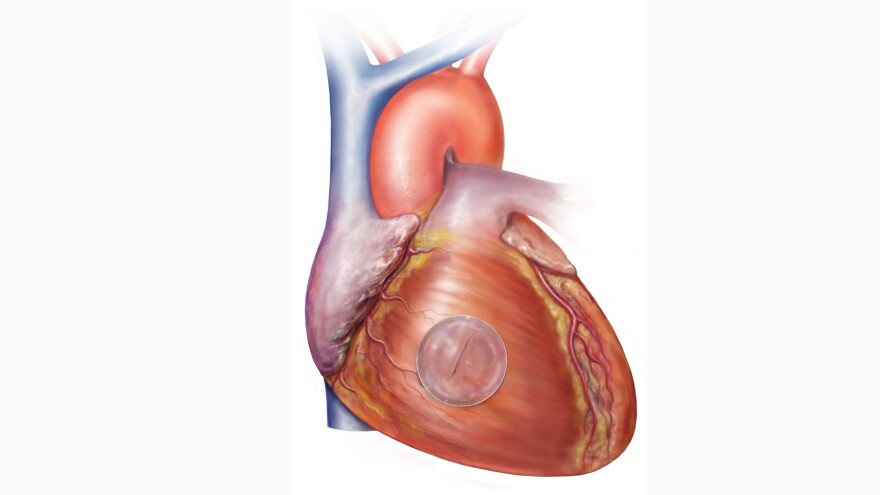

Cardiac surgeon Pedro del Nido and his colleagues have developed a biodegradable adhesive that can patch a hole in a pig's heart or artery. The experimental glue is nontoxic and is strong enough to hold up under the high pressures in the human heart, the team report Wednesday in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

So far, they've tested the glue only in animals. So the sealant is far from reaching the operating room or battlefield. But del Nido hopes the adhesive will eventually replace traditional sutures and staples for some operations, especially heart surgery.

"A glue is the holy grail for repairing hearts," del Nido tells Shots. "Right now we use sutures. Every time the needle and thread enter normal tissue, they do a little bit of damage. Usually it doesn't matter. But I repair children's hearts. For those, this damage can really be a problem."

Regular superglues don't work well inside the body. "It's a skin glue," del Nido says. "You can't use it internally because it hardens as soon as it comes into contact with water." And the glues are made from a compound called cyanoacrylate, which can be toxic.

To find a safe adhesive that could work on hearts, arteries and other organ surfaces, del Nido teamed up with bioengineer Jeffrey Karp, also at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

"In our lab, we look to nature for inspiration in designing materials," Karp tells Shots. "Solutions are really all around us." Karp's lab has been looking at porcupine quills for insights that could lead to better surgical needles.

For the heart glue, Karp and his team turned their attention to critters that stick to slippery surfaces, such as slugs, spiders and a bristly little worm that glues itself rocks in tidal pools, called the sandcastle worm.

"We started looking at how creatures, like the sandcastle worm, could attach to wet surfaces," Karp says. After years of experimenting with various chemical cocktails, he and his team finally stumbled upon an adhesive that's biodegradable and nontoxic.

"Cells and tissues can grow over the material and into it," he says. Eventually it just dissolves into the body. And the glue only hardens when UV light shines on it. So a surgeon can put the glue in exactly the right place before it seals up.

Although Karp and del Nido haven't tested the experimental glue on people yet, they've put the adhesive through a whole battery of tests in animals.

"We made a hole in the heart of a living rat and showed that we can seal it up without removing the blood," Karp says. "The animals were fine six months later."

They also patched a pig's heart and carotid artery with the glue. Even after the pig was given a shot of adrenaline and its heart pressure shot through the roof, the patched stayed on the tissue.

Of course, humans are more complicated than pigs and rats. And the glue has to be safe for decades in people, not months.

But Karp is so confident that the adhesive will one day reach surgeon's toolbox that he has procured $11 million to start a company to manufacture and test the glue. "It appears that the glue is safe," he says. "But we do need to do more studies. We'll repeat the animal tests and then move forward in humans."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.