We'll be releasing the results of this year's Summer Reader Poll on Comics and Graphic Novels later this week — and it's a varied and deeply idiosyncratic list, trust us. Y'all have some fascinating favorite comics.

Not to spoil anything, but the final list skews heavily toward recent offerings, which makes sense: The stuff that's been around a long time may earn people's respect, but new discoveries spark excitement. And that's what any survey that asks folks to name their favorites will naturally turn up.

But we wanted to round out the poll results by highlighting some of the comics that served as milestones, over the years. (Later this week we'll also feature some of the most important and influential old-school comic strips from the earliest days of the form.)

The comics listed below are the game-changers — they opened the medium up in one way or another. Maybe they found new audiences for comics. Maybe they changed how creators and readers approached the form.

We're not talking about plot twists, here, or we'd include a book like Saga of the Swamp Thing #21, for reasons some of you understand very well. Not that kind of game-changer. No, these comics fundamentally changed something more than a single character or storyline. They changed how the entire medium of comics was perceived.

Note: Some of these comics will appear in the final Summer Reader Poll results, others won't. Check back in on Wednesday.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Nothing Was Ever The Same: 10 Comics That Changed The Game

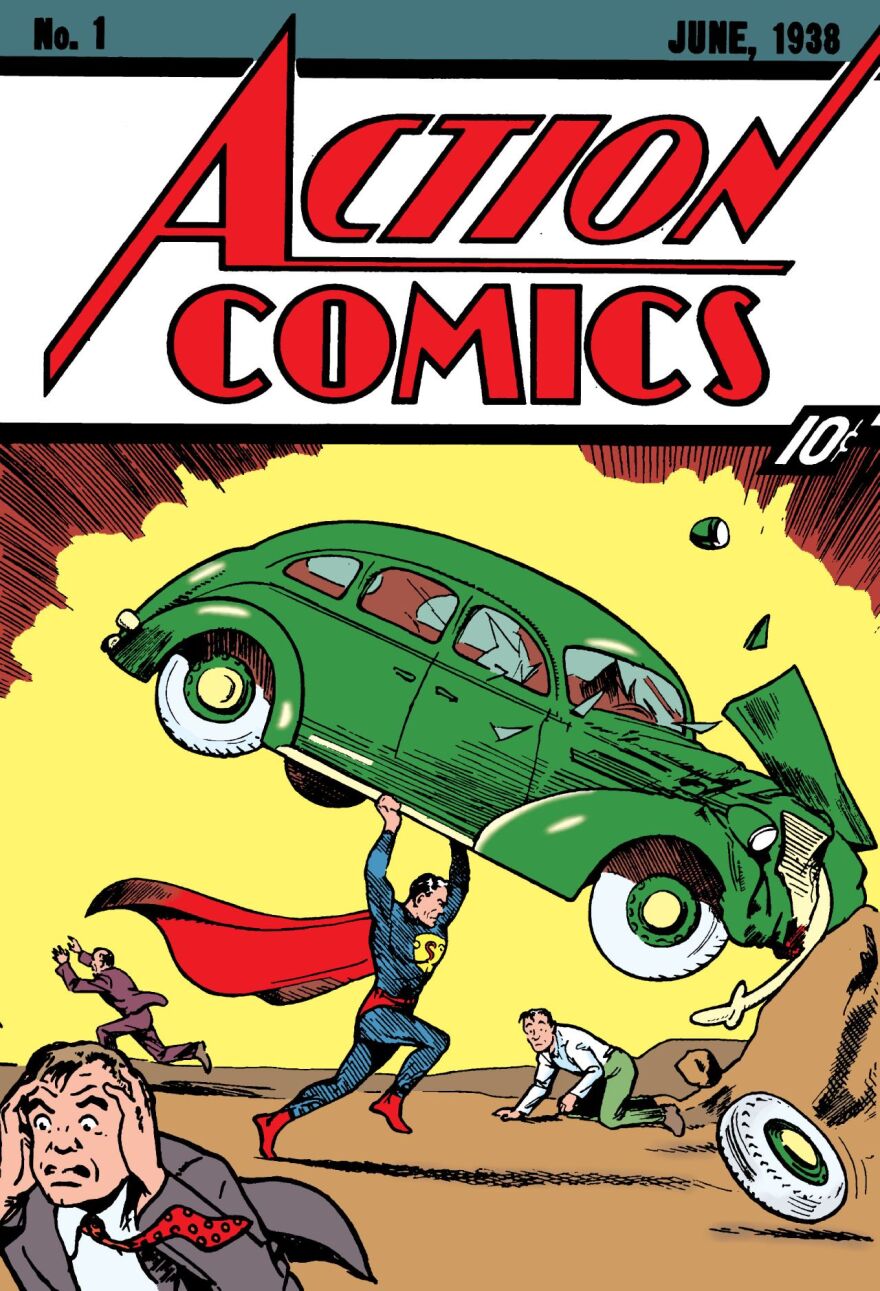

1938: Action Comics #1

by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster

Well, you probably saw that coming. A good case to be made for 1939's Superman#1, which was the first comic book entirely devoted to a single character, but Action Comics #1 was where that character debuted, alongside several other stories starring heroes who've been lost to history. (If Superman hadn't been a hit, would one of those other heroes have become a marketing phenomenon on his scale? Is there an alternate universe in which I'm typing these words in a Sticky-Mitts Stimson t-shirt?) Superman's runaway success inspired hordes of imitators in boldly colored longjohns. Collectively, those imitators became the genre of storytelling that still, decades later, dominates the comics medium — and, more recently, the worldwide box office. For better or for worse.

1952: Astro Boy

by Osamu Tezuka

Astro Boy (in Japanese, Tetsuwan Atomu, or Mighty Atom) was the brainchild of Osamu Tezuka, the master of Japanese manga. This series, about a flying robot boy with a big heart, wasn't his first work, or his best — but it remains his most iconic. The book's approach — its visual style, action, and character-based storytelling — became hallmarks of manga. Also, an animated series based on the comics series aired in syndication in many US markets in 1963; it was, for millions of Americans, their first exposure to Japanese animation. It would not be their last.

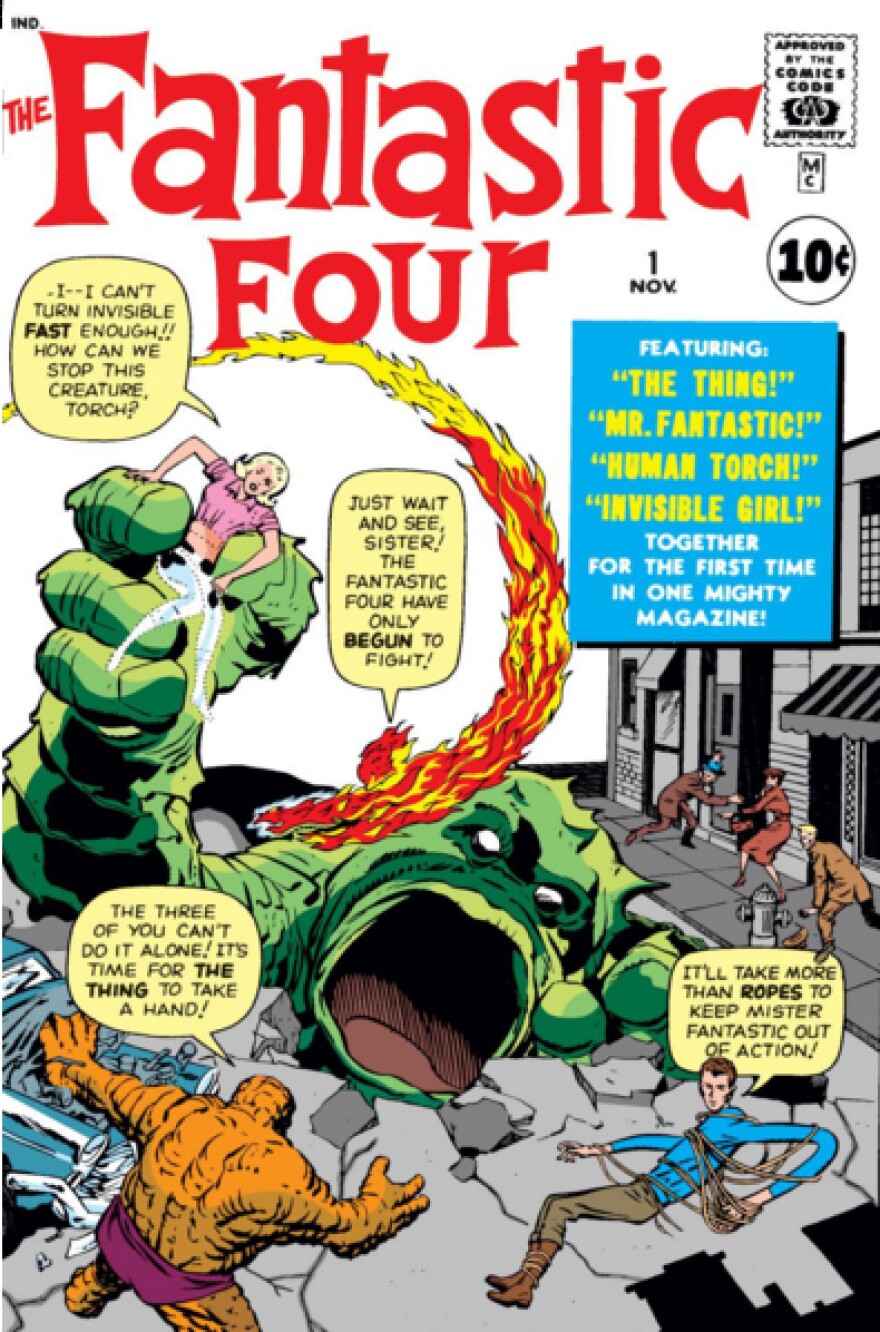

1961: Fantastic Four #1

by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee

What Stan Lee and Jack Kirby unleashed, on the pages of Fantastic Four #1 in 1961, looked, at first glance, a lot like the kind of standard super-hero fare that DC Comics had been serving up for decades. Until you read it. These were no stolid, do-gooding cyphers, no cops-in-capes. This was a collection of individuals who came to their astounding powers by accident. They bickered. They fumed. They gave in to feelings of resentment and jealousy, and they often didn't even seem to like each other much. Which is to say: They were a family. Deeply relatable, in a brand new way, to a brand new audience that didn't look like the young children who, just five years before, made up comics' core audience. No, these were teens and adults, who wanted heroes that weren't perfect and powerful, but flawed and freakish. Which would become the Marvel brand.

1968: Zap Comix

by R. Crumb, S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez and Robert Williams

Zap Comix didn't create the underground comics scene, but it's a classic example of the form, given its preoccupations: drugs, sex, music, and freakin' out the normals. Home to a stable of some of the most influential members of the counterculture comics movement, led by Robert Crumb, Zap thumbed its nose at everything square and polite, from superheroes ("Wonder Wart-Hog, the World's Smelliest Superhero!") to ... pretty much everything else, really. Also: Issue #1 gave the world the "Keep On Truckin'" guy. (Ask your parents.)

1978: A Contract With God

by Will Eisner

The great Will Eisner's work on his strip The Spirit had been showing the world the innovative narrative potential of the comics form for decades when he published this collection of stories set in and around a Lower East Side tenement building. But with A Contract With God, he doubled down, slapping the words "A Graphic Novel" — a term which had been percolating in comics circles for several years — on the cover. He'd later go on to write a treatise making the case that comics could tell any kind of story — but in a very real sense, with this collection, he'd already won the argument.

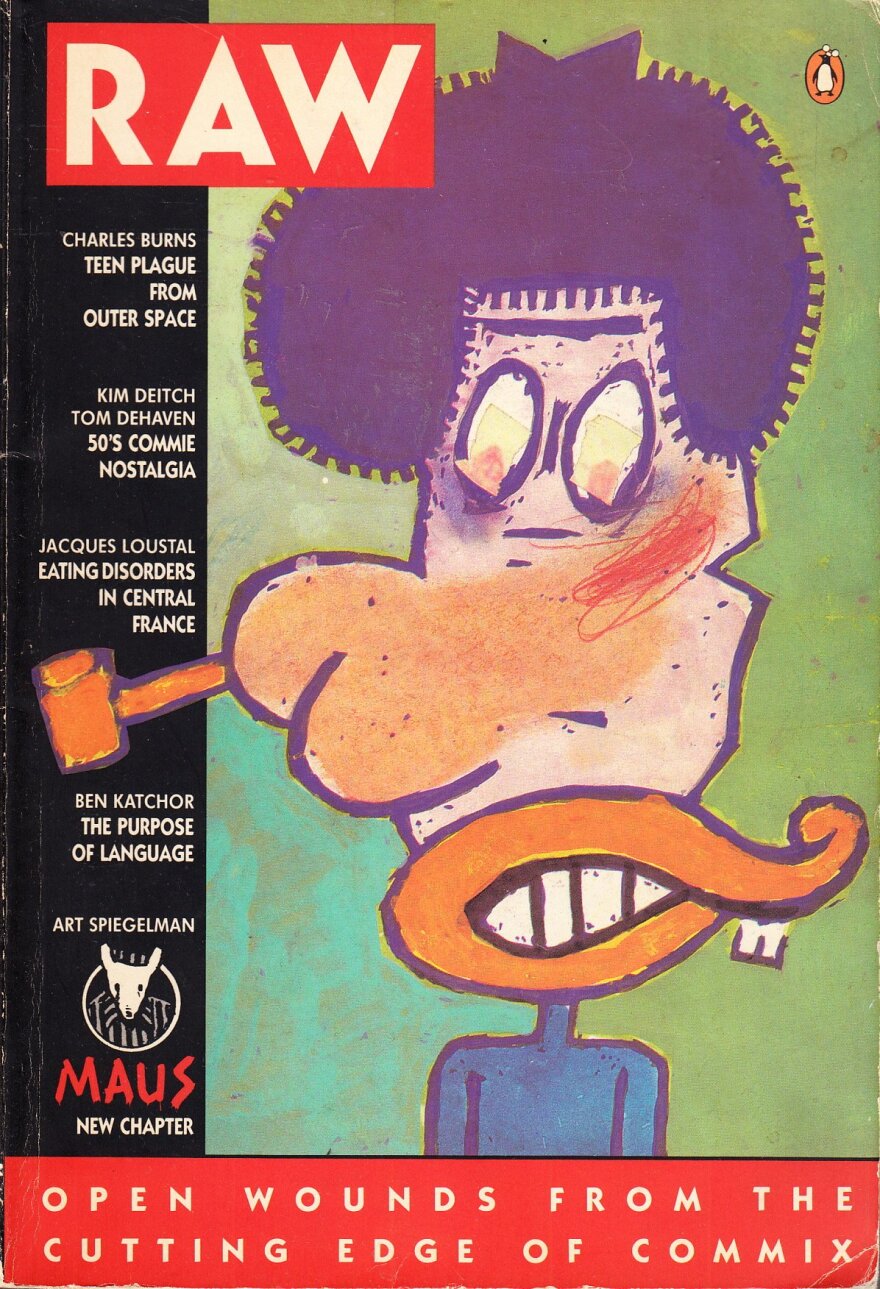

1980: Raw

by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly

The alternative comics scene of the 1980s was an explosive, politically charged and aesthetically varied one, and Raw — a comics anthology magazine edited by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly — was its gorgeously edgy epicenter. Not only did it regularly put the work of many European creators in front of American eyes for the very first time, it was home to the serialization of that game-changiest of game-changers, Spiegelman's epic historical memoir, Maus. Once Maus was eventually collected and published on its own, it would become fodder for thousands of "Comics Aren't Just For Kids Anymore!" articles, win the Pulitzer Prize and — oh, yes — fundamentally reshape how millions of Americans thought about comics.

1986: Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns

by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

We're assigning these two very different comics the same slot on this list because they arrived more or less at the same time, and had roughly the same effect on comics. Which is to say: their collective deconstruction of the superheroic ideal ushered in a wave of imitators, and the birth of the "grim and gritty" tonal shift that lingers to this day.

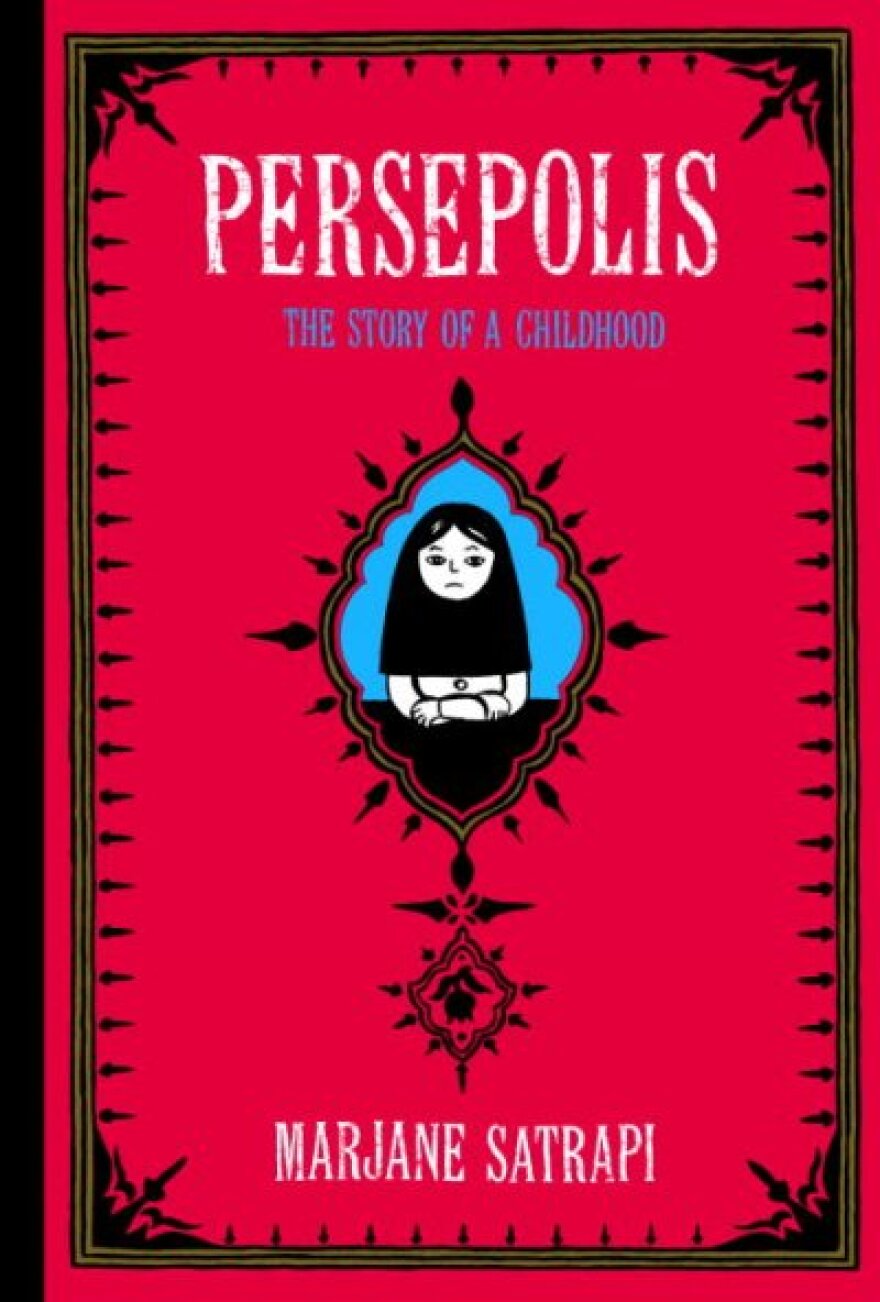

2000: Persepolis

by Marjane Satrapi

Arriving as it did amid a cresting wave of prose memoirs, Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis managed to carve out a space all its own. In this searchingly felt chronicle of growing up in Iran while the Islamist Revolution swirled around her family, Satrapi used black-and-white illustrations to distill a lifetime of conflict both personal and geopolitical. The two-volume work brought to millions of readers a world they did not know, with a perspective — a strong, clear, new voice — that could not be ignored. And wasn't. To a fresh generation of readers, it served as an reminder that there's a world beyond spandex, where urgent, nuanced stories are being told.

Special Citation - 1993: Understanding Comics

by Scott McCloud

Putting Scott McCloud's extended treatise — in comics form — about the craft, construction and aesthetics of the comics medium on this list seems awfully meta, but then: The book's about as meta as it gets. There's no denying that for noodges like me, who make it their life's work to get more people reading comics, it's a seminal text: fun, breezy, rigorously argued, and comprehensive.