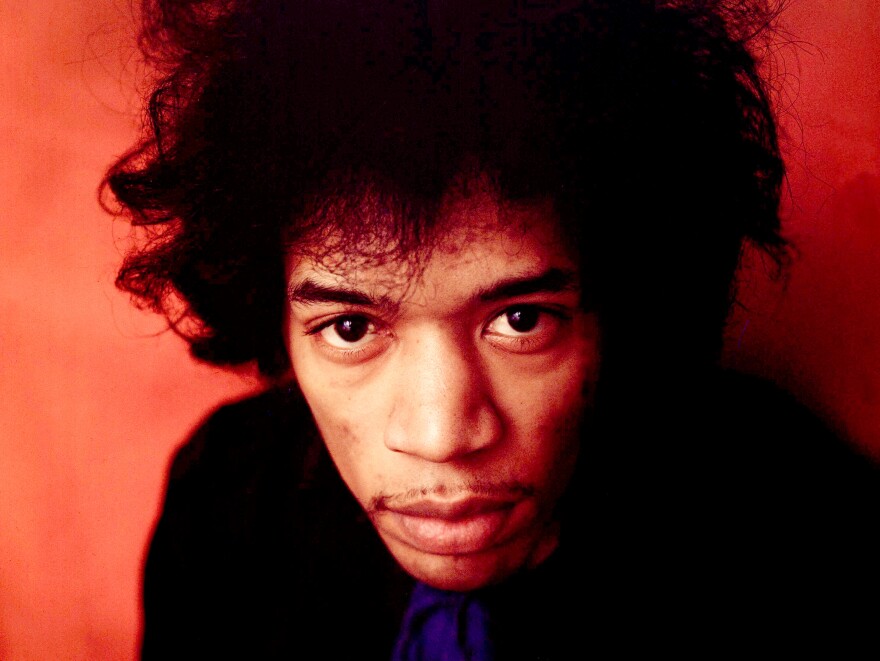

The Beatles finished recording their self-titled double album — "The White Album" — on October 17, 1968, the same week that The Jimi Hendrix Experience released their own two-record set, Electric Ladyland. This week, both albums are receiving lavish box-set treatments to commemorate their 50th anniversaries, including a remastered version of Electric Ladyland, new stereo mixes of "The White Album," 5.1 mixes of both, unreleased outtakes and rehearsals and books with photos, studio notes, and essays. For fans, it's a fascinating dig down the rabbit hole.

Both of these albums remain a challenge. They're long and messy. Hendrix and the Beatles had hit artistic and popular peaks in the fall of '68 and you can hear them flexing their muscles, using the power they'd earned to take refuge from the pop touring cycle, hole up in the studio, experiment and learn. The songs are disparate in style, including jams, sound effects, and special guests. It's as if they wanted to stuff everything they were creating in that moment into one record, less worried about fit and concept than creativity. Both albums stretched the possibilities of what rock music could do on a recording. They stand for artistic freedom and control in a way that few albums before them had achieved.

"The White Album" and Electric Ladyland also came after periods of personal upheaval. Brian Epstein, the Beatles manager, died in August 1967. Hendrix's manager, Chas Chandler, quit during the recording of Electric Ladyland, frustrated by the long and freeform sessions. But the loss of Epstein (and The Beatles' four-year run at the top of the charts) allowed them to take more control of the recording process. Hendrix, meanwhile, was able to produce and "direct" his own work, in close collaboration with his engineer Eddie Kramer. Loss turned to almost unchecked creative abandon.

The Beatles producer George Martin described these changes in a 1968 interview included in the "White Album" box set book: "It's rather like the students revolting in France. Youth is realising its power. It was very much the boss and they were the pupils. This naturally changed with their success and power. They want more say about what goes on."

Martin's analogy between The Beatles' independence and the student uprisings of May 1968 is an apt context for understanding the artistic confidence of these albums. But these rock stars were a lot more confused and vulnerable when it came to the politics of the time. "The White Album" and Electric Ladyland don't avoid politics, but Hendrix and The Beatles sound unsure about how to deal with the fact that their music is now in dialogue with what sounds like revolution: John Lennon's ambiguous "count me out/in" in "Revolution 1," and Paul McCartney's subtle-to-the-point-of-vagueness reference to civil rights in "Blackbird." Hendrix's "House Burning Down" wonders about the point of riots, and yet he introduces the September 1968 Hollywood Bowl concert included in the box set by creating feedback he describes as "celebrating the call of the Black Panther." The violence and upheaval of 1968 are all over these albums as they fluctuate between confidence and confusion. Their scale and complexity feel open-ended and challenging, and their dark moments a little scary. Kinda like now.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.