Ablaye Ndiaye made the long journey from Dakar, Senegal, to the Special Olympics World Games in Berlin, Germany to play basketball. But the 35-year-old's personal highlight during the week-long Games didn't happen on a basketball court. It was on the track of Berlin's Olympic stadium, where Ndiaye carried the blazing Olympic torch during the opening ceremony on June 17. A rapturous crowd of 50,000 cheered him on.

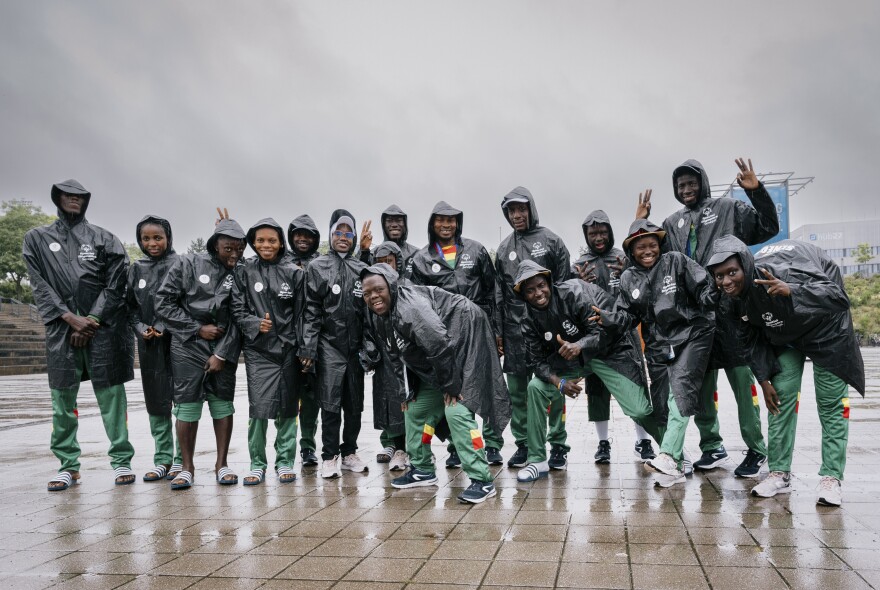

"Holding the torch at the opening ceremony was a great moment," Ndiaye told NPR on Friday, two days before the end of the games. It's little surprise that he was selected as one of a handful of athletes to participate in the final relay leg of the torch run. The captain of Senegal's 34-athlete delegation, Ndiaye has an affectionate ease with his teammates and coaches, and his celebratory dances during basketball games have become iconic enough to make the World Games highlight reels. His charisma is evident at the end of this video about Senegal's performance at a recent tournament.

"Ablaye provides the team with energy, he brings joy. He's basically the face of the team," said Yoro Ndiaye, team Senegal's basketball coach.

While many of the Senegalese athletes have intellectual disabilities – including Ndiaye, who has Down syndrome – the basketball team is "unified," an inclusive mix of athletes with and without disabilities. The Special Olympics features unified competitions and supports unified sports locally to help build social inclusion.

According to Yoro Ndiaye, this mix is indicative of the Senegalese delegation's wider dynamic. "[Here at the Games,] we don't see a difference between athletes and coaches. The whole delegation is one team. Not even just the basketball team. We do everything together," he said.

Intellectual disability in Senegal

Unfortunately, the Senegalese delegation's cohesive, tightly-interwoven nature doesn't reflect the reality for many living with intellectual disabilities in the country.

"It's very difficult in Senegal for people with intellectual disabilities," said Rajah Diouri Sy, national director of Special Olympics Senegal. Sy argues that this is especially true when it comes to educational opportunities. Inclusive education, which puts all students – both with and without disabilities – together in classes is a rarity. Research has shown that students with disabilities benefit from being integrated into mainstream schools rather than segregated.

"Most of our (inclusive) schools are private. And they are expensive. It is difficult for families to take their children to private schools. In both Dakar and other regions, we lack schools for people with intellectual disabilities," she continued. According to the nonprofit group Humanity & Inclusion, children with disabilities in Senegal are nearly twice as likely to be out of school than those without disabilities.

Sy's first involvement with the Special Olympics came through her daughter Khadija, who has Down syndrome and became a track and field athlete in 2004. Now Rajah has run the organization's Senegalese outlet for more than a decade, overseeing growth from just six athletes to roughly 3,000 today.

"There's a stigma in Senegal for children with intellectual disabilities, which we are trying to fight. Most of the time, people will blame mothers if a child has an intellectual disability. This often leads to people hiding children with intellectual disabilities. But things are starting to change now," said Sy.

A victory at the Special Olympics

Special Olympics Senegal aims to break that stigma down as well as connect young people with intellectual disabilities to broader networks of care. In addition to organizing teams in eight different sports, it partners with health-care providers, government agencies and NGOs to facilitate services like free health screenings, subsidized follow-up care, educational referrals and support for parents. For Sy, it's especially important that this effort isn't limited to Dakar, the capital.

"We are trying to engage more athletes and be present in their communities. We say that athletes don't come to us, we have to go to them," she said. According to the World Bank, Sub-Saharan African disability rates are higher in rural areas.

Special Olympics Senegal's primary focus remains sports, which Ndiaye's coach argues is strategic. "Sports can help develop both intellectual and physical abilities and capacities. It also gives our athletes an opportunity to interact with others and have a place in society," Yoro Ndiaye said.

Building confidence in athletes is just as important to the organization as connecting young people to more traditional services. Thanks to the organization, athletes in Senegal have become assistant coaches and found jobs. According to Rajah, two athletes recently got married.

Ndiaye, who works in construction and lives with family members, says he has built the confidence to expand his social circles and fit in.

"I've made friends in the Special Olympics, and I also have new friends in my community. People are more engaged, I interact with more people. I feel like I don't face as much discrimination because I am really part of my community," he told NPR.

His warm, humor-infused relationship with his teammates and coaches illustrates his point and puts Sy credo into practice. Ndiaye ensured that even down periods in an exciting, if long week for the team were filled with laughs, quick to crack jokes with teammates and coaches.

"We must continue to work to fight discrimination and isolation. That's the main aim of the Special Olympics. It's always inclusion," said Sy.

There's much work to do until the fight is won in Senegal and beyond. But it's definitely a victory to see Ndiaye and his teammates laughing together between games in Berlin's sprawling, ordinarily-drab exhibition grounds, a Special Olympics venue that has been given a jolt of life by the masses of colorfully-uniformed athletes, volunteers and spectators.

Ndiaye and his teammates weren't without their victories on the court, either. Senegal bested France on Saturday to win the bronze medal in 5-on-5 unified basketball. "My family is very proud that I'm part of the Special Olympics and have come [to Berlin] for the World Games," he said prior to the pivotal game. And now there's a medal to boast about as well.

Dave Braneck is a journalist in Berlin covering sports, politics and labor. His Twitter handle is @braneck

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.