Not so long ago, if you overheard a political conversation about isolationism, you assumed it was about the past.

Popular in the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of America going it alone in the world — politically, economically, militarily — was discredited after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor forced the U.S. into World War II in 1941.

Pearl Harbor prompted such leading isolationists as Sen. Arthur Vandenberg, R-Mich., to reverse themselves and become advocates of what he called "international cooperation and collective security for peace." That conversion "took firm form on the afternoon of the Pearl Harbor attack," the senator wrote. "That day ended isolationism for any realist."

That was conventional wisdom for more than 70 years, embraced by Democratic and Republican presidents alike.

But the term and the concept of isolationism are not consigned to the past anymore.

That is why on Friday, Vice President Kamala Harris addressed an international security conference in Munich, Germany, and repeatedly referred to isolationist sentiments as resurgent in the U.S.

"These are questions the American people must also ask ourselves: Whether it is in America's interest to continue to engage with the world or to turn inward," she said.

While she did not name former President Donald Trump in her public remarks, Harris left little doubt as to her ultimate target.

"There are some in the United States who disagree" with the global leadership role the United States has played, she said. "They suggest it is in the best interests of the American people to isolate ourselves from the world" and "embrace dictators and adopt their repressive tactics, and abandon commitments to our allies in favor of unilateral action."

She called that world view "dangerous, destabilizing, and indeed, short-sighted" because it would "weaken America and would undermine global stability and global prosperity."

Trump had stoked the discussion earlier this month when he told a rally in Conway, S.C., that he would "encourage" Russia to do "whatever the hell they want" to any NATO country he regarded as delinquent in its payments to the alliance.

Disavowing mutual defense

Beyond misrepresenting the way NATO is financed, Trump was disavowing the central purpose of the mutual defense pact. Article 5 of the 1949 treaty states that an attack on one member will be considered an attack on all.

It was a notably bald restatement of what Trump has been implying for years, although rarely with such stark language. Trump's stance on NATO has gained importance as the alliance expanded in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, which has never been in NATO.

Practically within the same news cycle, a majority of Senate Republicans voted against a bill that would send another $60 billion in U.S. military aid to help Ukraine repel that Russian invasion — along with lesser amounts to Israel and U.S. allies in Asia.

Among them was Ohio's J.D. Vance, who was elected in 2022 with Trump's backing and has been saying for months the U.S. should not write "blank checks" for Ukraine.

Some of Vance's GOP colleagues had other issues with the bill, but the underlying question was the underlying necessity of U.S. involvement in these conflicts.

And while the aid bill ultimately passed the Senate with a bipartisan 70 votes, it has hit a wall in the House. Speaker Mike Johnson has said he will not bring it to a floor vote because it does not address the situation at the U.S. southern border. An earlier attempt by the Senate to enact a bipartisan compromise on the border issue was opposed by most Republicans and rejected by Johnson.

One could say former Vice President Mike Pence foresaw the moment last October when he was still a candidate for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination. Responding to the Hamas attack on Israel, Pence blamed weakness in the U.S. in both parties, including Republicans "who have embraced the language of isolationism and appeasement."

Echoes of the past

In a sense, Trump and his supporters in Congress and in parts of the media have been updating and restating the misgivings expressed by generations of Americans in the past.

George Washington famously warned the nation to "steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world" in his farewell address in 1796.

And that advice held sway for the next century and a half, even as the U.S. engaged in half a dozen declared wars and many other military expeditions on foreign soil during that time.

In April 1917, the U.S. entered what we now call the First World War. Much of the nation opposed that war, and when it ended the sense of its futility was widespread.

That disillusionment contributed to the Senate's rejection of membership in the League of Nations in 1920 and strongly influenced the decade that followed. In the 1930s, U.S. participation in trade wars deepened the worldwide depression but only strengthened the appeal of isolationism for some.

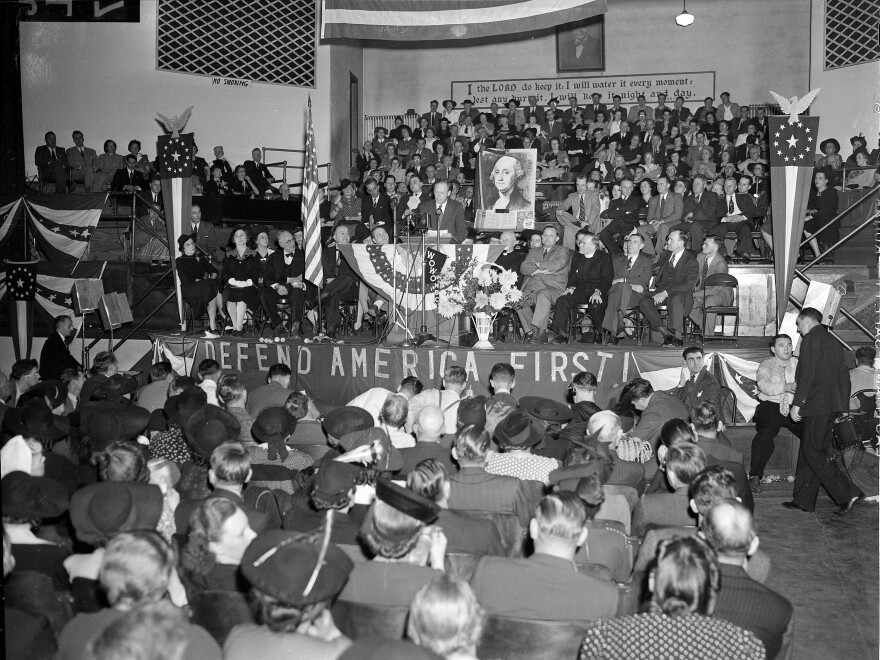

The America First Committee came to embody that sentiment. It was launched by students at Yale in the fall of 1940, as war raged once again in Europe and Asia and as Congress was voting for the first U.S. peacetime draft. The AFC claimed 800,000 members at its height. It included farmers, bankers and members of both major political parties, as well as individuals with more extreme views on the left and the right.

Its best-known members were Henry Ford, the automaker, and Charles Lindbergh, the aviator who had made the first solo trans-Atlantic flight. Ford was widely considered antisemitic and Lindbergh had traveled to Germany and expressed admiration for the Nazi regime.

But everything changed overnight with Pearl Harbor. Lindbergh called on the organization's members to support the war, and its leaders met to dissolve the organization three days after the declaration of war on Japan.

As they did so they released a statement saying: "Our principles were right. Had they been followed, war could have been avoided. No good purpose can now be served by considering what might have been, had our objectives been attained."

For a time, the phrase "America First" seemed an artifact of the prewar world. But the idea that the U.S. would do better for itself by holding the rest of the world at arm's length never left the political conversation entirely.

Pat Buchanan, a journalist and then a speechwriter for Richard Nixon, ran for the Republican presidential nominations of 1992 and 1996 before becoming the nominee of the Reform Party in 2000. The theme of his Reform Party campaign was "America First."

Donald Trump, who had briefly sought that same Reform Party nomination in 2000, launched his first bid for the Republican Party nomination 15 years later, adopting Buchanan's slogan. He also appropriated one from Ronald Reagan's 1980 campaign, dropping just the first word: "Let's Make America Great Again."

In the years since, the latter slogan, abbreviated as MAGA, has become part of the language. But "America First" has too, if to a somewhat lesser degree. It is commonly embraced by Republican candidates for a variety of offices.

Different reactions to wartime experiences

More than a few of these candidates at various levels have backgrounds in the active military and are veterans of deployments in Afghanistan, Iraq and other theaters of the "War on Terror." Their experience of those conflicts has influenced their attitudes toward an activist policy of foreign engagements.

That sets them apart from the veterans of World War II and the Cold War who generally favored not only international trade, but also a muscular military posture and aggressive responses to communist regimes around the world.

One consequence of that prevailing attitude was a long and costly war in Vietnam, with a subsequent pushback from the next generation of political leaders who had opposed that war. Some, such as longtime Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, the Democratic nominee for president in 2004, had served in Vietnam.

While the post-Vietnam pushback against foreign intervention came primarily from Democrats, in the 1990s many Republicans opposed President Bill Clinton's willingness to help allies in the Balkan War.

Some members of both parties resisted authorizing the first Persian Gulf expedition in 1991 (following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait) or the later invasion of Iraq in 2003. There was bipartisan support for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, at least initially, but it waned as those expeditions became occupations that went on for years costing lives and trillions of dollars.

Still, the main current of energy revitalizing isolationism today has a much older pedigree and features suspicion or rejection of international commitments including the United Nations, world trade organizations, free trade agreements and military treaties such as NATO that obligate the U.S. to fight on behalf of other countries.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.