(Editor's note: Both major presidential candidates this year are Protestants. Both of their running mates were raised as Catholics. Beyond that, their faith profiles are very different. We dug into the faiths of the Democratic candidates below and of the Republican ticket here.)

Tim Kaine, growing up in Kansas City, says his parents were such devoted Catholics that they did not let a Sunday go by without making sure their children attended church, even if it meant finding the one parish in town that offered a nighttime mass.

Hillary Clinton had a comparable religious upbringing in Park Ridge, Ill., where she and her family were regulars at the First United Methodist Church.

"Our spiritual life as a family was spirited and constant," the Democratic presidential nominee wrote in her 1996 memoir, It Takes a Village. "We talked with God, walked with God, ate, studied, and argued with God. Each night, we knelt by our beds to pray before we went to sleep. We said grace at dinner, thanking God for all the blessings bestowed."

For both candidates on the Democratic Party ticket, religious faith has provided a foundation for their progressive politics.

Kaine, now a senator from Virginia and Clinton's vice presidential running mate, has spoken often and comfortably about his Catholicism. But Clinton has been somewhat more reserved in discussing her religion. Though she regularly attended prayer breakfasts as a U.S. senator, her strong faith has mostly been a private matter.

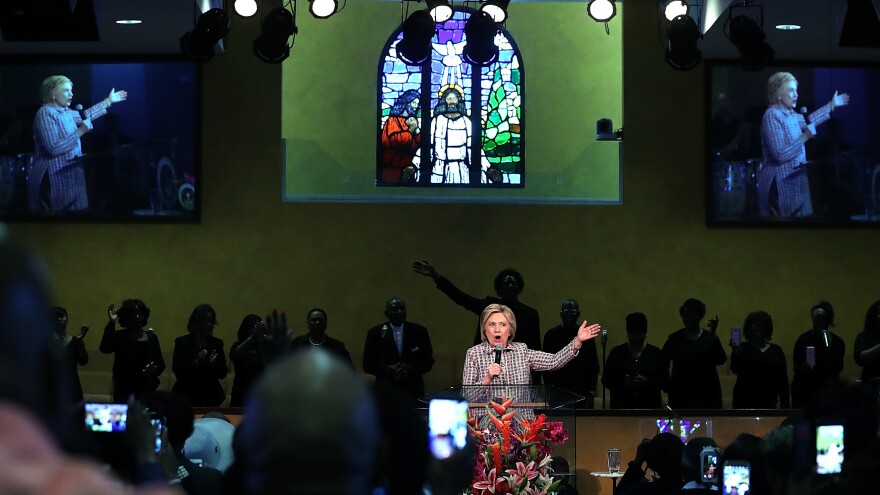

In a recent survey by the Pew Research Center, more than 4-in-10 respondents thought Clinton was "not very" or "not at all" religious. It is a perception she has sought to change during her presidential campaign. During a town hall in Iowa in January, Clinton spoke at length about her Christian views.

"My study of the Bible," she said, "my many conversations with people of faith, has led me to believe the most important commandment is to love the Lord with all your might and to love your neighbor as yourself, and that is what I think we are commanded by Christ to do. And there is so much more in the Bible about taking care of the poor, visiting the prisoner, taking in the stranger creating opportunities for others to be lifted up, to find faith themselves."

With that perspective, Clinton identified squarely with the "social gospel" of the Methodist tradition. It is an outlook encapsulated in the Methodist credo, widely attributed to the church founder, John Wesley: "Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can."

I was getting tired of the Catholic worship I was used to. [In Honduras], mass was two and a half hours long and it was so vibrant and chaotic and fun.

Clinton quoted that line in a September 2015 speech at the Foundry United Methodist Church in Washington D.C., the church she and her family attended when she was first lady. She also featured the quote in a recently released campaign video.

Clinton's statement that the "most important commandment" requires Christians to love their neighbors genuinely reflects John Wesley's teaching, according to Rev. Wendy Deichmann, a professor of history and theology at United Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio.

"John Wesley said you could have all the theological correct answers and yet really not be a Christian if you don't feel the love of Jesus Christ in your heart and actually practice that toward your neighbor," Deichmann said. It was a philosophy, she noted, that John Wesley exemplified during his own ministry in eighteenth century England.

"There's poverty; there's unemployment [and] alcoholism," Deichmann said, "and Wesley got involved in trying to address and requiring the people called 'Methodists' to help address those social concerns."

Among his other social and political causes, Wesley was a committed abolitionist at a time when slavery was still widespread.

The Methodist "social gospel" is so supportive of Clinton's own political agenda that it may be hard for some to distinguish her liberalism from the church teachings that she embraces. Theologians familiar with the "social gospel" tradition, however, recognize its historical authenticity.

"She is part of a historical denomination that is a Christian denomination," said Michael Farris, a conservative evangelical activist and a co-founder with Jerry Falwell of the Moral Majority. "It is much more politically and theologically liberal" than evangelical Christianity, he says, "but it is a real faith tradition."

The same can be said of Kaine's progressive Catholicism, which dates primarily from his years attending a Jesuit high school. In a recent C-SPAN interview, Kaine called his high school experience "a key part of my transition into my adult life. Instead of just accepting the answers of my parents of others. I've been a person who wanted to go out and find the answers on my own, and the Jesuits get credit for that. I do what I do for spiritual reasons."

Among Catholic orders, the Jesuits are considered the most liberal and socially conscious. Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pope, has highlighted his order's progressive profile through his advocacy for immigrants and the poor. Kaine has enthusiastically embraced that tradition, and in 1980 he interrupted his Harvard Law studies to work for a year at a Jesuit mission in Honduras, teaching carpentry and welding.

"It put me on a path," Kaine has said, and revived his commitment to Catholicism.

"I was getting tired of the Catholic worship I was used to. [In Honduras], mass was two and a half hours long and it was so vibrant and chaotic and fun. I learned how a strong spiritual life can help you deal with the challenges we face in life."

For the past 30 years, Kaine and his wife have been worshipping at a predominantly African-American Catholic church in Richmond, Va.

Kaine's faith profile in this respect mirrors Hillary Clinton's. Just as she comes from the liberal side of Protestantism, Kaine comes from the liberal side of Catholicism. Their candidacies raise the prospect that Democrats may have an opportunity to narrow the "God gap" they have had with Republicans. According to the Pew Research Center, Americans who see the Republican Party as "friendly toward religion" outnumber those who say the same of Democrats, by a margin of 42 to 30 percent.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.