The rain fell for days, sometimes 3 inches or more in a single hour, as streets became rivers and rivers ate up entire neighborhoods in southeast Louisiana.

Between Aug. 11 and Aug. 14, more than 20 inches of rain fell in and around East Baton Rouge, one of the hardest-hit parishes. And in some parishes in the region, as much as 2 feet of rain fell in 48 hours.

The National Weather Service says the likelihood that so much rain would fall in so little time was about one-tenth of 1 percent. A flood this bad should only happen once every thousand years.

As The Two-Way has reported, at least 13 people have died in the floods and some 60,000 homes were damaged. The Red Cross says it is likely the worst natural disaster since Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and that the response will cost at least $30 million.

As the water recedes, many local leaders, weather forecasters and Louisiana residents are wondering whether people could have been better warned.

Tracking the storm

How a storm develops dictates who is responsible for warning people about it.

This storm began as an area of low pressure over the Gulf of Mexico, where hurricanes are born, so from the beginning, the National Hurricane Center in Miami was monitoring it.

"Our job at the National Hurricane Center is to forecast the strength and size of tropical cyclones," explains James Franklin, the chief of forecast operations at the National Hurricane Center, who has worked on hurricane forecasting since the 1980s. He used to fly into storms as part of the agency's airborne reconnaissance team. These days, he tries to steer clear of tropical storms and help others do the same.

But this Gulf storm never became a hurricane. The wind speeds were very low. The middle of the system wasn't warmer than the edges, and air wasn't circulating around the center of the system the way it would in a cyclone.

So the National Hurricane Center did not issue an advisory.

This video shows NASA rainfall data from Aug. 8 to Aug. 15. More than 20 inches of rain fell in the areas depicted in pink on the map.

"If a disturbance or weather event is not a depression zone or a hurricane, we don't write advisories on it," Franklin says. "It's not our authority to write advisories on things that are not hazardous cyclones."

And he points out, "The best place to get local information is always the local office, even when the National Hurricane Center has written an advisory. The local office has the best information about local flood risk."

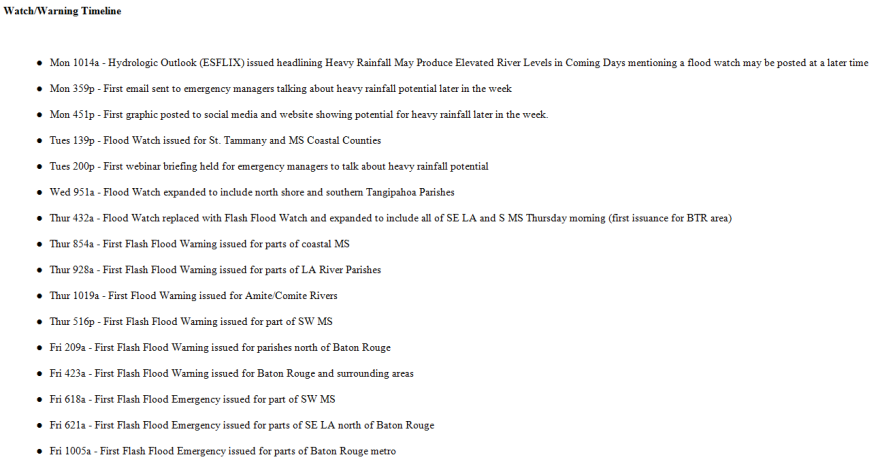

In this case, the local New Orleans/Baton Rouge National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office says it recognized the potential for flooding as early as Aug. 8. On that day — nearly three days before the storm arrived — it began issuing advisories and warnings about heavy rain. One rainfall map warned of "isolated flash flooding" later in the week.

Between Tuesday and Friday, when the first flash-flood emergencies were issued, the local weather service office for Baton Rouge says it issued at least a dozen advisories and warnings about flooding in southeastern Louisiana.

Kenneth Graham, the meteorologist in charge at the local office of the National Weather Service, says the situation was particularly difficult for forecasters trying to provide block-by-block clarity to residents. "We broke all records," he writes in an email to NPR. "For the River Flood Warnings, there is no way to reference any previous flood event since there is no history to draw from."

In the town of Denham Springs, the Amite River crested 4.5 feet above the previous record, and Graham explains that because the terrain is so featureless around Baton Rouge, "the water spreads out very far from the river," affecting an enormous area and tens of thousands of people.

By Aug. 11, Graham's office had decided to do something it rarely does — elevate the flash-flood warnings for areas around Baton Rouge to flash-flood emergencies, which can be issued only when there is significant and immediate threat to life and property.

Still, some residents say they were not adequately warned of the severity of the storm.

Baton Rouge resident Linda Smith tells Ryan Kailath of member station WWNO that she would have heeded more-urgent notifications. She and her family barely escaped their home before it flooded.

"We got no calls, no texts, no nothing," Smith says. "So that's why I didn't panic because I didn't hear a siren. I didn't hear anything."

It's important not to focus on the name or classification [of a storm], and instead focus on the hazards. Not everything that can be deadly or catastrophic is a tropical cyclone.

More than a dozen people died and no one was evacuated from the area before the most serious rainfall began.

The storm with no name

Tropical storms and hurricanes are assigned names by the National Hurricane Center, which draws attention to the storms. "There certainly is more visibility that comes from cyclone," says Franklin of the National Hurricane Center. One reason for that, he says, is that the name and category designations — such as Hurricane Katrina, Category 5 — are more likely to be picked up by the media.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards told the New Orleans Times-Picayune, "When you have a storm that is unnamed — it wasn't a hurricane, it wasn't a tropical event — people underestimate the impact that it would have."

"It's important not to focus on the name or classification [of a storm], and instead focus on the hazards," Franklin says. "Not everything that can be deadly or catastrophic is a tropical cyclone."

Franklin acknowledges that the National Weather Service shares responsibility for communicating storm hazards to the media. "There are often a lot of mixed signals out there, because the media is really focused on what [the National Hurricane Center] is saying about a storm, instead of the local office," he says.

The metrics that forecasters use to describe storms can also be confusing if people don't understand the on-the-ground effects of a storm in their neighborhood. Franklin says his agency is rolling out a new storm-surge-warning system next year to highlight that hazard more clearly.

But when it comes to communicating about flooding, he thinks the information forecasters provide is already pretty clear.

"We have some pretty good metrics for rainfall," he says. "It's called inches."

Many local newspapers, television stations and radio broadcasters in the Baton Rouge area began warning residents of potentially serious flooding on Aug. 11, the day the local NWS issued emergency warnings.

As for national media outlets, many were late to the scene and slow in their coverage.

Craig Fugate, the administrator for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, told the Times-Picayune newspaper last Tuesday, "You have the Olympics. You got the election. If you look at the national news, you're probably on the third or fourth page. ... We think it is a national headline disaster."

Reflecting on NPR's own coverage of the flooding, Vice President of News Michael Oreskes said it was both swift and thorough.

Oreskes says:

"As the water rose NPR turned to our member stations in Baton Rouge and New Orleans for immediate news coverage by Friday, Aug. 12. By that Sunday, NPR's Southern correspondent, Debbie Elliot, had arrived from her home in Alabama, navigating around floodwaters on remote parish roads to get into Amite and Baton Rouge."

The New York Times published its first story by a staff reporter on the evening of Aug. 14. Last week, the public editor of The Times published an apology for the newspaper's lack of timely coverage. She wrote:

"No doubt this is a busy news period, and the fact that it is August compounds the usual challenges of getting available staff to the site of the news. But a news organization like The Times — rich with resources and eager to proclaim its national prominence — surely can find a way to cover a storm that has ravaged such a wide stretch of the country's Gulf Coast."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.