Though the violence has ended in Charlottesville, Va., debates and protests continue and Confederate statues and monuments are being removed all over the country.

A 2016 report from the Southern Poverty Law Center found as many as 1,500 "symbols of the Confederacy" in the U.S. But who were some of the men memorialized with statues, monuments and memorials in a nod to the Confederacy?

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Finis Davis was born in Kentucky but grew up in Mississippi. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1828 and became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Seven years later, Davis resigned his military post after deciding to marry the daughter of his commanding officer — future President Zachary Taylor, who opposed the marriage. His wife, Sarah, died soon after they wed.

Davis became a cotton farmer and got involved in politics, eventually winning a seat in Congress in 1845. A year later, he resigned to go fight in the Mexican-American War, where he was wounded and earned the admiration of Taylor, his former father-in-law and former commander.

Davis was appointed to finish out the term of Sen. Jesse Speight of Mississippi, who died while in office. He served, was re-elected and became chairman of the Senate Military Affairs Committee.

After a failed run for Mississippi governor, Davis was appointed secretary of war by President Franklin Pierce. He traveled between the North and South, giving speeches calling for harmony.

But Davis was also a staunch advocate for states' rights — and when Mississippi seceded from the Union in January 1861, he resigned with a speech defending slavery:

"When our Constitution was formed, the same idea was rendered more palpable, for there we find provision made for that very class of persons as property; they were not put upon the footing of equality with white men--not even upon that of paupers and convicts; but, so far as representation was concerned, were discriminated against as a lower caste, only to be represented in the numerical proportion of three fifths."

A few days later, Davis was chosen as provisional president of the Confederacy. On Feb. 18, 1861, he was inaugurated. He sent a peace mission to Washington, but President Lincoln refused to see his emissaries. A month later, Davis sent Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard to Fort Sumter, S.C., and the Civil War began in earnest.

Davis had a troubled presidency. He didn't get along with his vice president and he didn't listen to Beauregard, who wanted to take the fight to the North. He didn't do enough to rally his constituency and he ignored advice to offer freedom to slaves in exchange for fighting for the Confederacy. To the latter, he argued: "African slavery, as it exists in the United States, is a moral, a social, and a political blessing."

But as months grew into years and money, food and armaments waned, Davis changed his mind about allowing slaves to be soldiers. He began "to embrace the idea that this is the only way in which the Confederacy stands any chance of surviving," author Bruce Levine told Fresh Air's Terry Gross in 2013.

"Partly I think it is simply a reflection of the state of desperation," Levine said. "Anything is better than what we face because what we certainly face is defeat, so how much worse might this be? At least we can try it, I think is one strand of Confederate thinking. But another factor is the drumbeat of self-hypnosis that the Confederacy has been keeping up during the entirety of the war. A message contained in that self-hypnosis is that the slaves are loyal. The slaves embrace slavery. The slaves are contented in slavery. The slaves know that black people are inferior and need white people to oversee their lives. Black people, therefore, are grateful for our care of them. Black people will defend the South that has been so good to them."

Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in 1865, bringing on the end of the war.

Davis was captured, imprisoned and charged with treason but was never actually tried. He went on to write The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government and A Short History of the Confederate States of America. He died in his bed in 1889.

Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee, a native of Stratford Hall, Va., resigned from his U.S. Army commission to fight for Virginia and the Confederacy in the Civil War. According to Roy Blount Jr., author of Robert E. Lee: A Life, the general opposed Virginia's seceding, but once that decision was made, he had to do what he felt was honorable.

"[Lee] went with his people. He thought of Virginia as his country more than he thought of the United States as his country. It was not a good career move," Blount told The Washington Post in 2007. "Also, his wife would never have forgiven him if he hadn't gone with the South."

In an interview with NPR's Neal Conan in 2011, historian Noah Andre Trudeau said, "Lee was a typical Southerner who really, I think, had a very complex approach, understanding of slavery.

"On the one hand, they could tell you to your face it's a terrible thing," said Trudeau, who authored Robert E. Lee: Lessons In Leadership. "On the other hand, they couldn't really think of any alternative. That is, it was the way of life, it was the way of law [and] therefore we just have to learn to live with it."

Though he surrendered the Confederate Army at Appomattox, after his death five years later, in 1870, Southern leaders would turn Lee into an icon to save face.

Gen. Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, another of Virginia's native sons, was a graduate of West Point and fought for the U.S. in the Mexican-American War. He left the Army to teach at the Virginia Military Institute, but when the Civil War broke out, Jackson joined the Confederate Army and became a colonel for the Virginia militia. He earned his nickname of "Stonewall" in the Battle of First Manassas, also known as the Battle of Bull Run.

Jackson was shot accidentally by his own men at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia on May 2, 1863, and his arm had to be amputated. He died of pneumonia eight days later.

An editorial in The New York Times after his death described Jackson as "a man of narrow mind, but of tremendous will and indomitable purpose; and he flung the great energy of his nature into all that he undertook."

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

Roger B. Taney served in the Maryland House of Delegates, the Maryland state Senate and as the state's attorney general.

His support for President Andrew Jackson earned him an appointment as U.S. attorney general in 1827. Seven years later, when the Senate declined to confirm Taney's nomination as Treasury secretary, he returned to his home state of Maryland to practice law — but not for long. A year later, President Jackson nominated him to the Supreme Court.

His nomination languished until Chief Justice John Marshall died and Taney was nominated to fill his seat. He was sworn in as chief justice of the United States in 1836.

Taney is best-known for writing the majority opinion for the Dred Scott case, ruling that slaves could not be U.S. citizens, even if they were freed.

In 2010, Justice Stephen Breyer called Dred Scott "the worst case ever decided" in an interview with Fresh Air's Terry Gross.

"That was a terrible decision," Breyer said. "And the only justification I've ever heard for it was that Roger Taney, the chief justice, and the majority thought that by deciding that, they would avoid the Civil War. It happened the opposite way. They fed the flames of the Civil War."

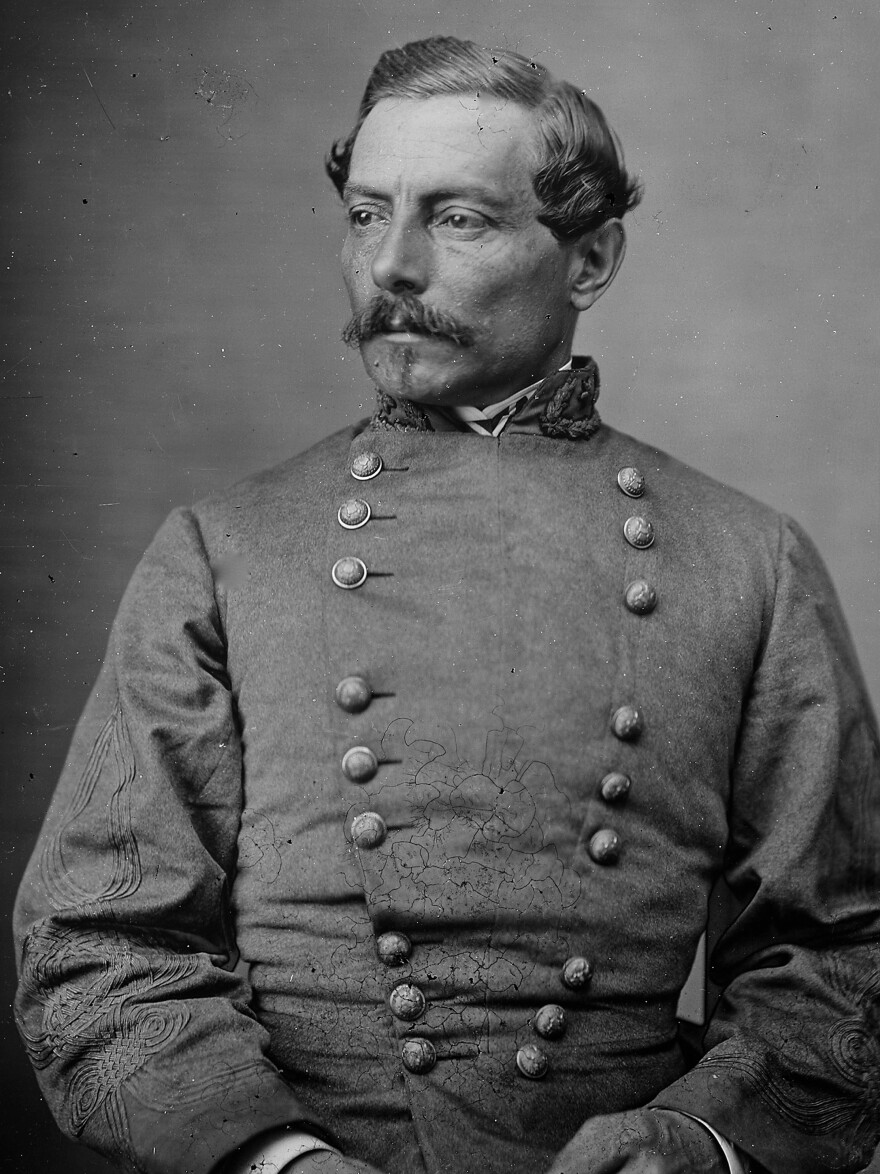

Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard

Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard hailed from Louisiana. He, too, was a West Point graduate and like his contemporaries Jackson and Lee served in the Mexican-American War.

He had just been appointed as superintendent of West Point when Louisiana seceded from the Union. Beauregard left and became a general for the Confederate Army.

He was commander of the troops that routed Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired. As former NPR librarian Kee Malesky told NPR host Scott Simon in 2011, "Federal troops, under command of Maj. Robert Anderson, surrendered to Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard after an artillery bombardment."

Beauregard played a key role in the Battle of First Manassas and at other major skirmishes including the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee and the Siege of Corinth in Mississippi. But according to The Washington Post, he "bickered with superiors, especially Confederate President Davis. ... That feud with Davis continued for years, and in 1889 when Beauregard was asked to lead the cortege at Davis's funeral, he refused."

Brig. Gen. Joseph Finnegan

Joseph Finnegan was born in Ireland and immigrated to Florida. He was a lawyer and farmer who owned a lumber company and built railroads.

He had strong political connections and was commissioned as brigadier general in the Confederate Army in 1862 and given command of the District of Middle and East Florida. Two years later, Finnegan claimed a victory in the Battle of Olustee. He was transferred to Virginia to serve with Lee, then later sent back to Florida, where he served until the end of the war.

After the war, he became a Florida state senator.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.