General Motors workers made big concessions to help pull the automaker out of its 2009 bankruptcy. Now, the company is making record profits.

But, the Warren Transmission plant in Michigan shut its doors at the tail end of June, and most of the workers have been placed at other plants. It's a ghost factory.

This scenario is playing out at GM's Detroit-Hamtramck, Baltimore Assembly, and Lordstown, Ohio, factories, all closed or due to close soon, with displaced workers heading to factories miles or hundreds of miles away. Consumers aren't buying cars, which these plants made. They are buying SUVs and trucks. So GM has excess plant capacity when it comes to cars.

Danielle Murry, a former Warren Transmission employee, says the closure is a slap in the face.

"I was happy to ... save my job, to save the company that I work for," she said. "Now that they're on top, and still making record-breaking profits, they're not willing to do that for us, to save us."

Murry is still waiting to hear from GM. She will have to accept whatever job offer she gets, even if it's a transfer to Tennessee or Texas.

The shutdowns are a big thorn in the side of United Auto Workers members and thus, union negotiators, as the UAW will soon sit down at the bargaining table with GM.

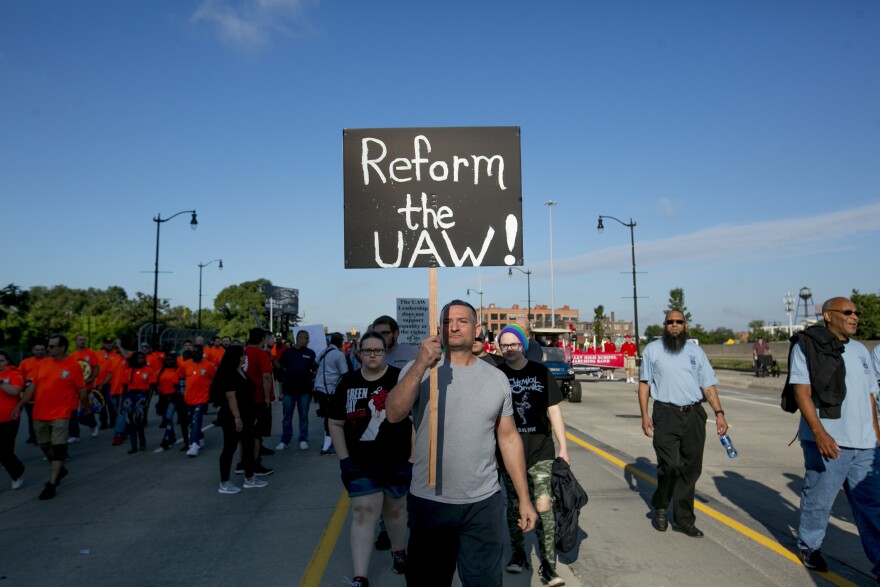

And the timing couldn't be worse. A years-long FBI probe into corruption at the highest levels of the union led to convictions for five UAW officials. The investigation widened in August and, for the first time, a UAW official in the GM division was charged with fraud for bribes and kickbacks.

Earlier this month, reports surfaced that the FBI was investigating allegations of lavish junkets paid for with union dues by current UAW President Gary Jones and the former president, Dennis Williams. The corruption probe is almost certain to undermine union workers' trust in their leaders.

"They have to make sure that everything they do is pristine," said Peter Henning, a law professor at Wayne State University and former federal prosecutor. "They had better get a good deal for their membership. I wonder whether the membership is going to trust the agreement that they reach?"

There are other thorny issues, too. Blue collar jobs at General Motors, Ford and Fiat Chrysler — the Detroit Three — come with a profit-sharing check in good times, but workers have gotten only two 3% raises in the past decade, according to Kristin Dziczek with the Center for Automotive Research.

It's also a big source of resentment that workers hired after 2007 get paid less and don't get a pension. Then there's the automakers' heavy reliance on temporary workers, which make up nearly 9% of the Detroit Three's blue collar workforce.

Dziczek says the threat of a strike if the union can't move the needle on these issues is very high.

Michael Hicks, an economics professor who focuses on manufacturing, agrees.

"There is a very high probability of a strike," he says.

Hicks gives the union poor odds of getting GM to agree to things that increase its labor costs.

"I mean, we're staring at a manufacturing-led recession, especially in the Midwest," he says. "The UAW's timing couldn't possibly be worse."

And even if the union does get wage increases from GM — and that's a long shot — the union's expectation is that other automakers and auto suppliers will follow the pattern. They may not be able to afford it. There's a lot at stake, Hicks says, for a lot of workers.

"That ongoing dance between GM and the UAW is really a proxy for almost 400,000 workers and hundreds of firms across the country," he says. "I don't see a real way out for the UAW... we're staring a global recession in the face."

If members don't like what their negotiators bring to them — if they don't trust it's the best they can get — a strike, damaging to the UAW and GM, could ensue.

Copyright 2019 Michigan Radio