Pretty much every medical organization has told men to back off on screening for prostate cancer, because it can lead to unneeded treatment, including surgery that can leave a man incontinent and impotent.

But it's hard to resist a robot.

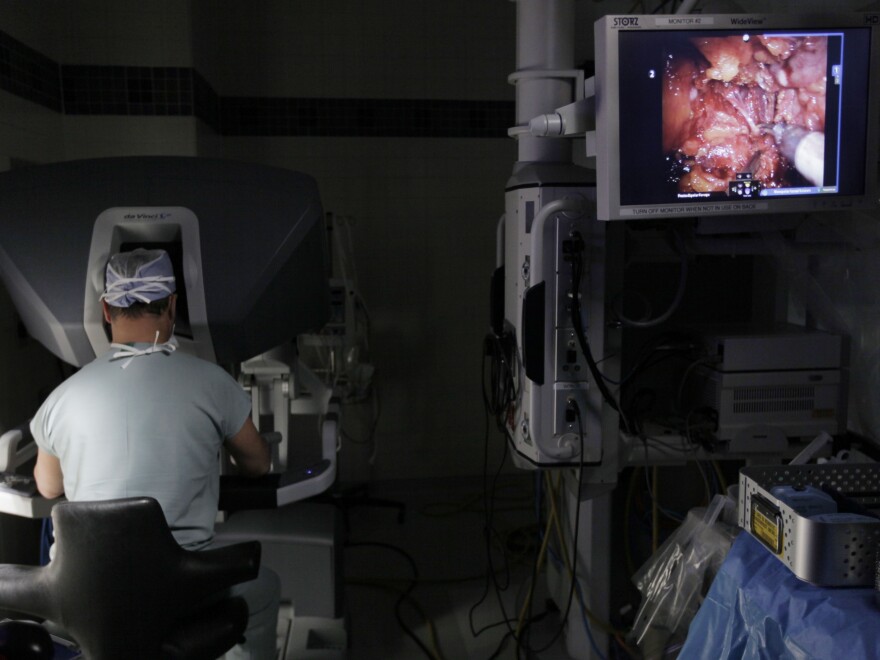

Men who have been diagnosed with low-grade prostate cancer increasingly choose expensive newer treatments including robotic surgery and a radiation treatment called intensity-modulated radiotherapy, or IMRT, even though they are not likely to benefit from those treatments, according to a study in JAMA, the journal of the American Medical Association.

Use of the newer treatments rose from 32 percent to 44 percent between 2004 and 2009 among men with low PSA test scores or other indications that their prostate cancer was slow-growing and didn't pose a threat.

Use also increased among men who were older or in poor health and were likely to die of something other than the cancer. Their use of robotic surgery and radiation therapy almost doubled, from 13 percent to 24 percent. Men older than 65 with low-grade prostate cancer have a 20 percent chance of dying of the cancer in the next 20 years, compared to a 60 percent chance of dying from something else, the researchers said.

Robotic surgery and radiation treatment are marketed heavily as offering fewer side effects and easier recovery, but as with most new treatments there's little evidence that they are better than established treatments.

Earlier this year the nation's gynecologists said women shouldn't have hysterectomies with robotic surgery, because there's no evidence the robots do as good a job as other forms of surgery.

The new treatments for prostate cancer are much more expensive than traditional forms of surgery and radiation, and are drawing increasing scrutiny from payers like Medicare. The data for this study came from Medicare records of treatment for more than 83,000 men who had not been diagnosed with other forms of cancer.

So cost is a concern. But more troubling is the idea of men choosing treatments they don't need, robot or no robot, that can have harmful side effects.

"For men with low risk, observation would be preferred to intervention, whether with robotic surgery, traditional prostate surgery, or IMRT," says Dr. Timothy Wilt, a researcher for the Veterans Administration who studies treatments for prostate cancer but wasn't involved in this study. Despite that, he notes, "patients are receiving and doctors are recommending treatments that are no more effective, no safer, and much more costly."

One way to avoid the lure of new treatments is to screen for prostate cancer less frequently, Wilt tells Shots. "The more we look, the more we find. The more we find, the more we treat. Because we look so hard, we find things that might never cause problems."

Last year the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force said that no men should have routine prostate cancer screening with the PSA test, because low-grade prostate cancer is so common, and the risk of being given unnecessary harmful treatments is so high.

And last month, the nation's urologists said the prostate-specific antigen test isn't needed for most men, suggesting testing only in men at high risk and those ages 55 to 69. Even those men should get tested no more than every two years, the urologists said, rather than annually.

But men who have been tested and found to have low-grade prostate cancer may find it hard to resist the lure of treatment, especially if it's being touted by a physician.

Even though most doctors say watchful waiting is a good strategy for low-grade prostate cancer, two-thirds of urologists and radiation oncologists recommend treatments rather than observation, according to a 2012 study.

A primary care provider can help sort out the pluses and minuses of prostate cancer treatment versus observation, Wilt says. "They're not selling a procedure," he says

He adds: "It's really important that medical care is driven by good science, and that we should be cautious about assuming that something must be better just because it's newer."

Tell that to the robot.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.