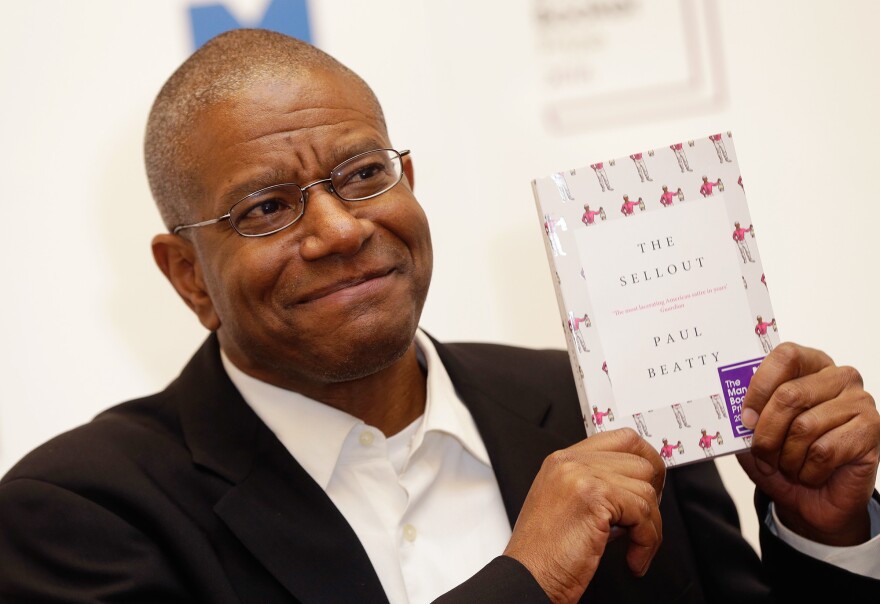

In his belligerently funny novel The Sellout – the first American novel to win Britain's top literary award, the Booker Prize – Paul Beatty eviscerates racial politics in the U.S. by aiming some of his sharpest stabs at that old and vicious shaming device: the food slur.

Aware that racism, like an army, marches on its stomach, Beatty, a 54-year-old poet-novelist who writes in the satirical tradition of Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Pryor and hip-hop, weaponizes watermelons, fried chicken, chitterlings and other foods used to slander and shame blacks, even as he cracks lethal jokes about poverty and respectability politics.

Here's how a classic Beatty bon mot explodes: "Your mama been on welfare so long, her face is on the food stamp."

The plot that powers The Sellout is as gloriously blasphemous as the language it employs, with the black narrator, Bonbon, determined to break Brother Mark Twain's record of using "the n-word 219 times" in Huckleberry Finn. Bonbon is being tried before the Supreme Court for reintroducing segregation in his hometown and owning a slave – transgressions that are especially impolite in the "post-racial world" of America's first black president.

His defense is that he was forced to violate America's sacred creed of racial equality after Dickens – his agrarian ghetto hometown outside Los Angeles – was erased from the map for being, well, such a Dickensian eyesore. In order to make Dickens great again, Bonbon has resorted to political incorrectness. He's distributed "No whites allowed" signs and agreed to own an old black actor named Hominy who begged to be his slave.

Bonbon is an urban farmer who specializes in weed and watermelon. He's chosen these crops for their "cultural relevance." That's a caustic euphemism for the marijuana-related mass incarceration of blacks and parade of malicious watermelon slurs directed at them, from 19th-century caricatures to NAACP police-violence protestors in Missouri being greeted with a racist cornucopia of a melon, fried chicken, beer and a Confederate flag.

"The watermelon has always been associated with blacks, because it's indigenous to Africa and slaves would grow them in their kitchen gardens," explains Fredrick Douglass Opie, professor of history and foodways at Babson College. "But the hurtful watermelon stereotype dates back to the post-Civil War period of Reconstruction. During this time, there were more African-Americans serving in public office than at any time in American history. And to undermine them, stereotypes were created – that blacks are lazy and childish, that they can be bought for fried chicken and watermelons, and that they're incapable of being good citizens or public officials because all they care about is their stomachs."

Beatty has played hardball with watermelons before, and has gotten into trouble for doing so. In 2006, he put an image of a half-eaten slice on the cover of Hokum, an anthology of African-American humor he'd edited. Meant to resemble a smile, it only raised hackles. Bookstores balked, as did black culture magazines Ebony and Essence. But Beatty was unapologetic. It's satire, he said, get over it.

The Sellout is sticky with watermelon nectar, reflecting Beatty's disregard for the sensitivities of "bougies" (Bourgeois Blacks), derided in the novel as the "Dum Dum Donut Intellectuals," who want to "disinvent the watermelon."

"Beatty's novel has shades of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, and I get why he's being so bodacious in using these tropes," says Opie. "But I can also see that it would upset black elites and even other folks. For instance, when I was growing up, it was an unsaid rule in my house that you would never, as an African-American, be seen eating watermelon in front of your white colleagues. We enjoyed it at home, but not outside."

Food shaming is a theme Beatty touches on in his first novel White Boy Shuffle, where the narrator writes: "Black was hating fried chicken even before I knew I was supposed to like it."

Bonbon, too, talks about "the racial shame that makes a bespectacled college freshman dread Fried Chicken Fridays at the dining hall." His college may have trumpeted him as their "diversity" student, "but there wasn't enough financial aid in the world to get me to suck the gristle from a leg bone in front of the entire freshman class."

This incident was rooted in a real-life encounter. As Beatty told the New Statesman shortly after winning the Booker, "I did a reading once at a small college, and I was talking to some students afterwards. There was a young black woman there, and she was saying they had Fried Chicken Fridays at the college, and she was like, 'I love fried chicken, but there's no way I'm eating some fried chicken in front of all these white kids on Friday,' you know? You want some chicken but you can't eat it. For me, that's a really good illustration of just the layering of bullshit that you have to deal with in life."

If Bonbon is an erudite radical, the eccentric Hominy, who begs to be flogged, is both pitiable and subversive. As a child actor, Hominy was a "stunt coon" and understudy of Buckwheat, the watermelon-loving black boy in The Little Rascals, the children's television series that Beatty watched obsessively, and whose "ragamuffin racism" sparked his novel.

"By calling his modern-day slave Hominy, Beatty is taking us all the way back to the antebellum period, when slavery was a legal institution," says Opie, who wrote Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America. "The two consistent staples that made up the diet of free and enslaved people were corn and pork in one form or the other.

"Of course, the 'master class' ate the best cuts of the pig, which is where you get the term 'eating high on the hog,' while the chitterlings – the intestines – were eaten by slaves who couldn't afford to waste any part of the animal," Opie adds. "Over time, chitterlings became a delicacy among blacks – it's very labor intensive to clean and cook them down – and now it's served at fine restaurants. But it's one of the foods blacks have been stereotyped with in the cruelest way."

Jokes from the "Chitlin Circuit" abound. In an acerbic riff on blackness and authenticity, Beatty skewers the Supreme Court's "Negro justice" whose robes seem "stained with barbecue sauce," "Michael Jordan shilling for Nike" and "Condoleezza Rice lying through the gap in her teeth," before offering a parodic prescription for "Unmitigated Blackness": "Tiparillos, chitterlings, and a night in jail."

Though Beatty now lives in New York, he grew up in Los Angeles, and can't resist lobbing a few heirloom tomatoes at his hometown's culinary mores. LA is described as "a mind-numbingly segregated city" where "you can find Korean taco trucks only in white neighborhoods," and where Beverley Hills epicureans seek to educate Bonbon on "the myriad ways in which a sweet potato can be prepared." No gastro-slouch himself, Bonbon deftly promotes chez plantation produce as "artisanal watermelons."

"Beatty is obviously messing with the foodies," laughs Opie. "I once called Malcolm X a foodie on my blog and got a comment saying this was such a classist term. The whole idea of food trucks and the 'eat local' foodie movement makes me so angry. As for Farm to Table – blacks have been doing this forever. And now, they're trying to introduce black folk to collards and kale and sweet potato just because they have the opportunity because of skin pigment to make money from these foods. It's ridiculous." (See the Neiman Marcus $66 collard greens debacle, for example.)

Beatty also lashes out at the minstrelsy tic writers have of deploying luscious food metaphors to portray non-white skin. "Honey-colored this! Dark chocolate that!" rails Bonbon's girlfriend. "My paternal grandmother was mocha-tinged, cafe au lait, graham-f******-cracker brown! How come they never describe the white characters in relation to foodstuffs and hot liquids? Why aren't there any yogurt-colored, egg-shell-toned, string-cheese-skinned, low-fat-milk white protagonists in these racist, no-third-act-having books!"

Full of humor, anger and pain, The Sellout has no safe spaces. "Humor is vengeance," Beatty wrote in Hokum, "... black folk are mad at everybody, so duck." Because a well-aimed, artisanal melon may be headed your way.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.