Last week, former NFL player Ryan O'Callaghan re-introduced himself to the world in dramatic fashion. In an article in Outsports, O'Callaghan revealed his harrowing experiences as a closeted gay man — and how his fear of being discovered drove him to drug addiction and a planned suicide.

O'Callaghan now is retired from the NFL and is open about his sexuality.

And suddenly he's a man very much in demand.

More than a week later, O'Callaghan still is fielding calls for interviews.

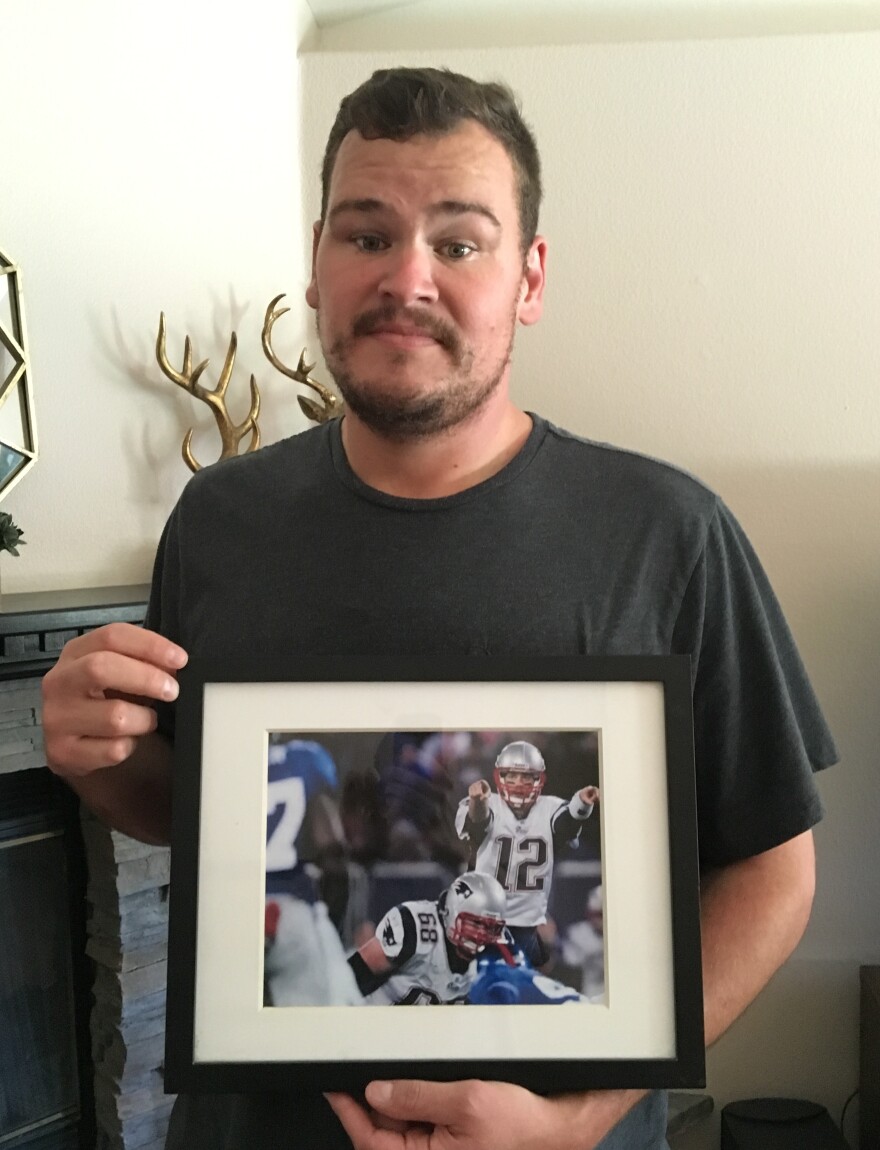

"I'm great, how are you?" he says to a producer from ESPN. O'Callaghan is sitting on a couch in his home, in his hometown of Redding, California. He's wearing a dark T-shirt and shorts and sporting a scruffy beard.

The network wants to tell his story exclusively, but O'Callaghan's not sure.

"My goal is to get the word out there as much as possible," he says to the producer. "So, you know, limiting it would kind of defeat the purpose."

The purpose of all this — telling his story of fear and lies — is to reach others. He already has, judging by the several thousand emails, texts and Facebook posts that have poured in since the Outsports article.

He scrolls through his phone.

"OK, well, here's a good one to read," he says. "It says, 'Hi Ryan, I think you saved my life today. I'm gay and have been living this lie for as long as I can remember.' "

"So he's married, has children," O'Callaghan continues.

The man's wife knows he's gay, but not his boys. He tells O'Callaghan he's been in therapy and has come to terms with who he is. But he needs advice on how to move forward.

"And like me," says O'Callaghan, "he's also thought about ending things."

No one will accept him

It's that dark subject that's made Ryan O'Callaghan's story resonate. A gay pro athlete coming out isn't as huge a story as it once was. But O'Callaghan was a gay pro athlete who planned to kill himself. Because in his mind, no one would accept him. Not family, not friends, not the NFL.

"I was going to shoot myself," he says quietly. "It was the easy way. I didn't look at it as being selfish. You know I used to think we all have the right to disappear. It's our body."

But before disappearing, Ryan O'Callaghan planned to be very public.

Football as a beard

A football career that started in high school as a way to stay connected to friends evolved into something much more in college. At Cal Berkeley, the 6-foot 6-inch, 340-pound O'Callaghan fully realized his plan to hide behind the sport.

Football, in his words, became his beard, his cover, an uber-masculine world where his sexuality wouldn't be questioned.

Maintaining the cover became his sole purpose in life. He started chewing tobacco. One night at a bar with teammates, he left with a young woman and made sure the teammates saw.

"That bought me a couple of years" of cover, O'Callaghan told Outsports.

"I thought a lot," he says. "I thought about everything. I had a plan. Football to me was deadly serious."

So was the suicidal end of the plan, once he was finished with football.

A good career cut short

But the end would have to wait. O'Callaghan was good at what he did on the field. In 2005, he won the Morris Trophy, an annual award for the top offensive and defensive lineman in the Pacific-12 Conference.

O'Callaghan is proud of the award.

"It's voted on by the defensive linemen [he faced during games]. That's why it's a good one."

Indeed, while football was "deadly serious," there were aspects O'Callaghan enjoyed — like the competition.

"I remember I was always happy at game time," he says. "Maybe because I knew everyone was so focused on the game and we got to compete. I felt that was a day when I wasn't going to be outed just because no opportunities, maybe."

After Cal, O'Callaghan was drafted by the New England Patriots and played on the team that almost went undefeated in the 2007 season, losing only to the New York Giants in the Super Bowl.

In total, O'Callaghan played six NFL seasons, for New England and the Kansas City Chiefs. His career was cut short by injuries.

As the end of his career — and in his mind the end of his life approached — he started abusing the painkillers he'd been us taking for all his injuries --- to his shoulders, neck, back, groin, not to mention numerous concussions.

Kansas City's head athletic trainer, David Price, noted O'Callaghan was behaving erratically. So Price suggested O'Callaghan meet with Susan Wilson. She was part of a network of psychologists the NFL employs nationwide.

"If Dave Price hadn't referred him to therapy, he may not be with us today," says Wilson, who no longer works with the NFL or the Chiefs.

Testing his fear

In the nearly 15 years she worked with the league, Wilson counseled other gay players who hid their sexual orientation. But she says O'Callaghan was the only one who wanted to kill himself because he was gay. When he finally came out to her, Wilson understood the depths of his despair.

"Even when he told me [he was gay], he said, 'And you don't hate me?' " Wilson says. "And I'm like, 'Ryan, of course I don't hate you.' "

Wilson advised O'Callaghan to test his fear that everyone would reject him. So several years ago, O'Callaghan started coming out to those he was closest to. Kansas City Chiefs General Manager Scott Pioli accepted him. So did his family, some of whom he'd heard use gay slurs when he was young. And so did close friends, like Eric Nielsen, who still remembers how O'Callaghan broke the news.

"He was kind of filling me in on how things went in Kansas City," Nielsen says, "then just kind of came out and said, 'Oh, by the way, [I'm gay].' It was kind of like an 'Oh!' but at the same time it wasn't like, 'No you're not' or 'You've got to be kidding me!' It was just, 'That makes sense.' "

The positive responses shocked O'Callaghan. Still, he needed time to fully emerge.

"I spent 29 not planning on living," he says. "I was a junkie on pain meds. You don't go from that to perfectly fine overnight. I didn't even date, I think, the whole first year after I came out. I worked on figuring out how to love myself and clean up my life."

Once he figured that out, it was time to come out to the world.

"I almost felt somewhat obligated [to make the announcement in Outsports] just because I'm a real good example of what not to do," O'Callaghan says. "If I can stand up and say hey, look at all this dumb stuff I did because I was gay, don't do it, I can save a lot of people a lot of heartache."

The reaction to his announcement has, again, been positive. Almost entirely. Some of O'Callaghan's former football teammates sent notes of encouragement.

Not always a field of roses

Wilson thinks O'Callaghan is showing closeted gay people from all backgrounds the value of overcoming fear.

But, Wilson cautions, there's also a danger in O'Callaghan's experience.

"Some people hear about this story," she says, "and think, 'Oh, I can come out and it's going to be a field of roses.' When we know some people are not in the situations where that will be the case."

The same goes for NFL players.

"I think the road has been paved," says Wilson. "You had [Michael] Sam. And now Ryan. The road is more paved now for a major player to come out — still reminding ourselves, however, that football is still a very masculine sport, a sport where masculinity is put on a pedestal. So I think we can't underestimate that, even though Ryan's story came out well. There still are pockets, in the fan base and elsewhere, that would feel otherwise about a major player coming out. [They] would feel angry or hostile about it even."

Ryan O'Callaghan says after so many years of hiding, he's ready to do what he can for those who still feel trapped. He hopes to write a book about his experience and raise money for LGBT charities.

And he plans to revel in living a life in full view.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.