Shen Lixiu's story is numbingly familiar.

Officials in the eastern Chinese city of Nanjing knocked down her karaoke parlor for development. She says they then offered her compensation that was less than 20 percent of what she had invested in the place.

Shen complained to the central government. Local authorities responded by sentencing her to a "re-education through labor" camp for a year. Once inside, Shen says, camp workers tried to force her to accept the compensation.

"I refused to sign my name," says Shen, 58, who has salt-and-pepper hair and wears a plum-colored, padded coat. "They beat me, knocked out my front teeth."

Shen reaches up and removes a set of false teeth. Her mouth forms a ghoulish grin with a dark gap where her four front teeth were kicked out.

She says fellow inmates beat her in exchange for reduced sentences — a practice human rights investigators say is common in these camps.

"Everyone went to sleep at night, not me," Shen recalls. "They gave me a small stool, forcing me to stand on it. Once you fell to the ground, people would come to beat you. They asked drug addicts and prostitutes to beat you up."

Those beatings proved effective. After seven months, Shen gave in. She signed the compensation agreement and was released, but she continues to protest what happened to her.

"I want to call on the leaders to abolish re-education through labor camps," she says. "Inmates can no longer be tortured like this."

'Like Profit-Making Enterprises'

In January, the Chinese government announced it would "reform" the nation's notorious re-education through labor camps. Under the current system, police can send people to the camps for years without trial, sometimes just for complaining about local officials.

"The system has drawn increasingly wide and fierce criticism from the public for years, and the need for reform is more necessary at present," read a commentary in China's state-run Xinhua news service last fall.

The government has yet to explain what reform would mean. However, the people who know the camps best — former inmates — say closing them is long overdue.

China's Ministry of Justice says 160,000 people were imprisoned in 350 re-education through labor camps at the end of 2008.

Inmates include prostitutes, drug users and people like Shen, who have petitioned the central government to try to redress the wrongs of local officials.

Local authorities often use labor camps to shut up their critics with minimal paperwork.

"Local officials don't want their dirty laundry to be aired in the open," says Maya Wang, a Hong Kong-based researcher for Human Rights Watch. "The police control the process. They don't have to go through the courts, and they don't have to present any evidence."

All they have to do is issue a document stating that an individual has disturbed social order, and that person can be sent to a camp for up to four years, Wang says. She adds, though, that actual sentences are shorter than they used to be and are now never more than two years.

The Communist Party built the labor camps in the 1950s to punish political enemies, including landlords and other capitalists. Today, the camps are driven by the same motives they were initially designed to punish.

"These re-education through labor facilities have become more like profit-making enterprises," Wang says, "for the local government to basically have free labor that they could force to work for many hours a day to produce products at very low cost for domestic and international consumption."

Desperate To Talk

Some former prisoners gathered recently at a dingy apartment buried among the alleys of south Beijing. They were so desperate to tell their stories that when a reporter arrived, they broke into applause.

The ex-inmates say they worked up to 16 hours a day making everything from circuit boards and uniforms to wire and blue jeans for little or no pay.

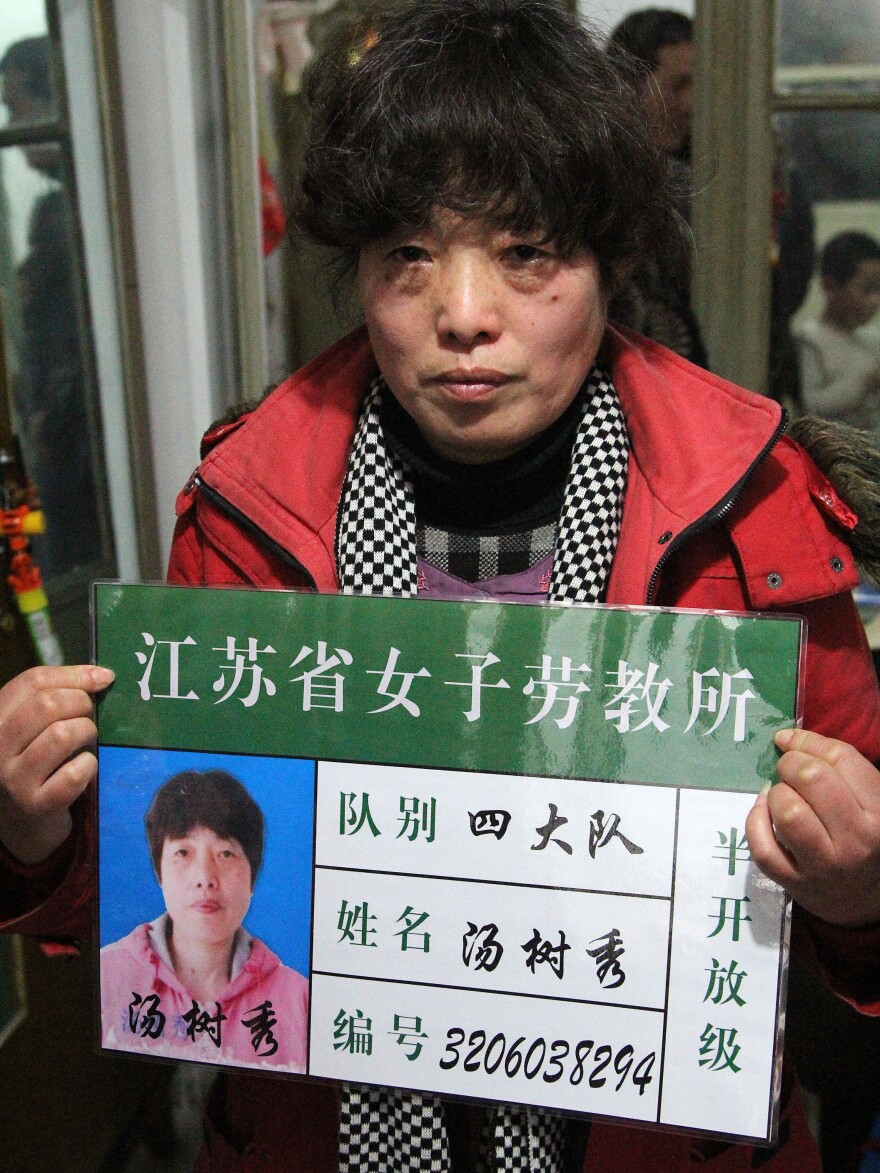

One of them, Tang Shuxiu, says she went to Beijing in 2011 to complain that her local government work unit hadn't given her an apartment to which she thought she was entitled.

Police picked her up before she got out of the train station.

"They asked, 'Are you here to petition?' I said, 'Yes,' " recalls Tang, who brought a mock-up of her labor camp identification card to pose with for photos so she can publicize the abuses of labor camps and push for change.

Tang, 51, says it never occurred to her to lie to the cops at the train station.

"I think petitioning doesn't mean I am doing something bad or committing a crime," she says. "I should tell the truth."

Like Tang, many petitioners are honest to their own detriment. Tang's candor landed her in a labor camp in eastern China's Jiangsu province for nearly a year. She says she spent more than 12 hours a day sewing the seams of blue jeans.

"When I first started making blue jeans, I worked slowly," she recalls. "Our team leader smacked my hands with his shoes. He said, 'These are all for export. You've got take it seriously.' "

'I Was Suffocating'

Tang was imprisoned for complaining about her housing. Sometimes, people are sent to labor camps for complaining about labor camps.

Hundreds of petitioners staged protests in Beijing during a visit by then-U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in 2009. Among them was Zhu Guiqin. Her brother had been put in a labor camp for alleged involvement in the banned spiritual group Falun Gong.

"On the day when Pelosi arrived, some petitioners and I tried to go to her event, and we were taken to the local police station," Zhu says. Police sent her to a labor camp in Shenyang, a city in China's frigid northeast.

Zhu is a wiry 49-year-old with a feisty personality who talks a blue streak. She says the guards eventually tired of her defiance and put her in solitary confinement — a tiny room with no bed.

"They confiscated my foam rubber mattress, saying, 'This is not a hotel. Are you here to enjoy your life?' " Zhu recalls. "They dismantled the radiator and let me sleep on the floor."

On winter nights, temperatures in Shenyang can drop below zero. Zhu wrapped up in a sweater, coats and quilts to stay warm. The room had no windows. Zhu says the air was awful.

"I couldn't breathe. I was suffocating," she says. "I lay on my stomach, facing the narrow space between the door and the floor to suck air from the outside."

Murky Meaning Of 'Reforms'

Stories like this have circulated on China's Internet, driving public opposition to the camps. One of the most recent cases involved Tang Hui, a woman from south central China's Hunan province. Tang was sent to a labor camp last year after criticizing police for trying to protect brothel operators who trafficked her 11-year-old daughter. The ensuing uproar on the Chinese equivalent of Twitter forced authorities to release Tang after just 10 days.

Wang Gongyi, a retired labor camp researcher with the Ministry of Justice, says the whole issue is way overblown. For one thing, he says petitioners only make up a tiny fraction of camp inmates. However, Wang does think the days of re-education through labor are numbered.

"I think it will probably be abolished, because the majority government people support abolition," Wang says. "The core of the problem is decisions are made arbitrarily. The system doesn't strictly follow legal procedure. Good people can be easily wronged."

Wang adds that many camps have already stopped taking prisoners.

"Now, people are only coming out, not going in," says Wang, "so the system only has 30,000 to 40,000 people."

With official policy still unclear, though, some human rights activists are skeptical. Maya Wang of Human Rights Watch wonders if officials will stop sending petitioners to camps, only to house them in illegal black jails.

"What we fear is that one system is gone and another system crops up," she says.

Labor camps still have one big group of supporters: China's police. For them, giving up an authoritarian tool that has proven so convenient for so long would be a big step.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.