The name Niccolo Machiavelli is synonymous with political deceit, cynicism and the ruthless use of power. The Italian Renaissance writer called his most famous work, The Prince, a handbook for statesmen.

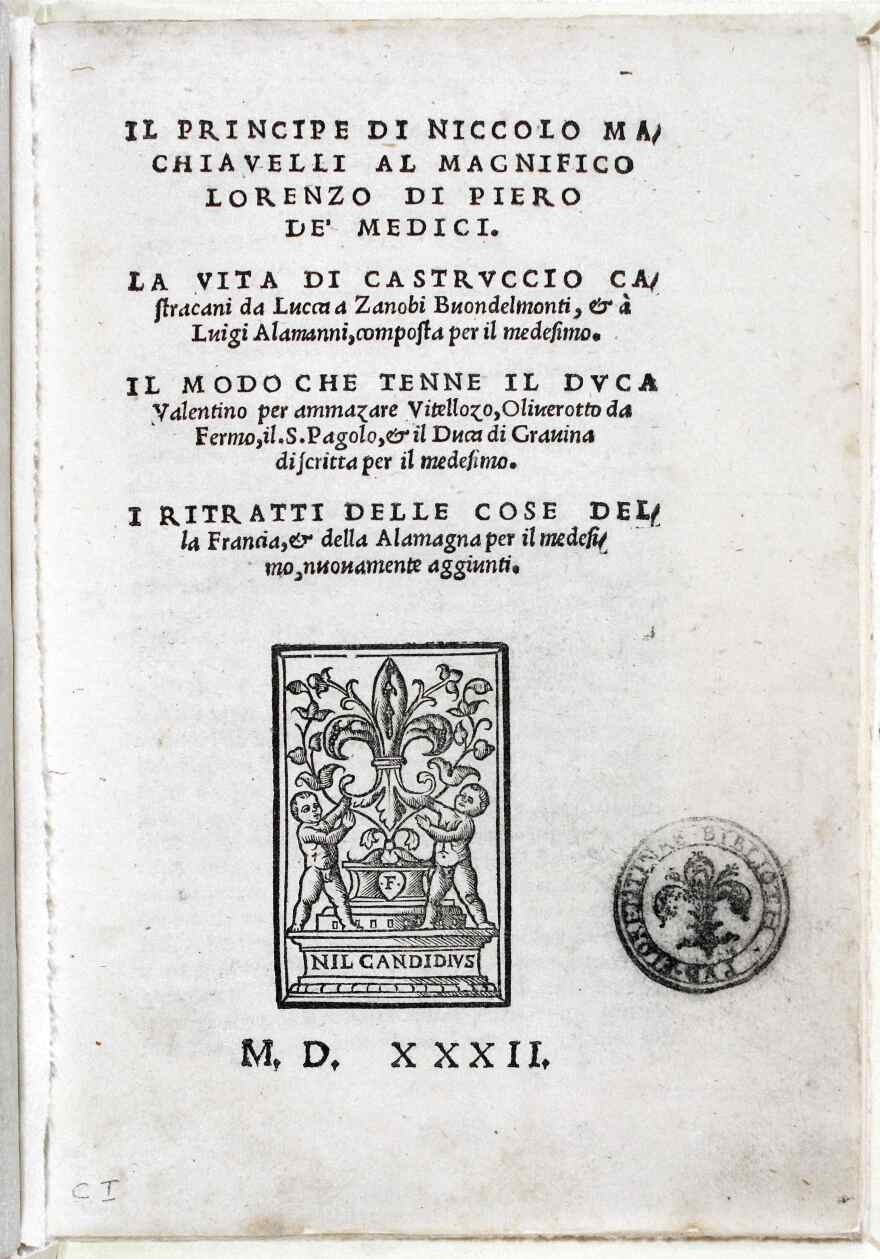

An exhibit underway in Rome celebrates the 500th anniversary of what is still considered one of the most influential political essays in Western literature.

Even today, The Prince continues to both fascinate and stir controversy.

The Catholic Church was the book's first detractor, so it's only fitting that the exhibit at Rome's Vittoriano museum includes an item loaned by the Vatican. It's a wooden chest from the Holy Office, once known as the Inquisition, where the index of banned books was kept.

But despite the ban, copies and translations of The Prince spread quickly throughout the known world of the time.

It's the most translated book from the Italian language — beating even Dante's Divine Comedy, according to the exhibit curator, Alessandro Campi.

He points to several display cases dedicated to what came to be known negatively as "Machiavellism."

"It all starts with the Elizabethans," says Campi. "There are several passages in Shakespeare and Marlowe that mention the Old Nick, a name for the Devil later applied also to Niccolo, the sinister Machiavel."

Pointers On How To Stay In Power

A politician, historian and philosopher in Renaissance Florence, Machiavelli wrote The Prince while he was virtually under house arrest.

He had served in the Florentine Republic in key positions, as a diplomat and the official in charge of the city's military defense, until the Medici princes were restored to power in 1512.

Later accused of conspiracy, he was arrested and tortured in prison. After he was released to his country home, politics remained Machiavelli's passion and he wrote what many scholars say is the first modern treatise on political science.

Here are some of his suggestions on how political rulers can stay in power:

-- "My view is that it is desirable to be both loved and feared; but it is difficult to achieve both and, if one of them has to be lacking, it is much safer to be feared than loved."

-- "The promise given was a necessity of the past; the word broken is a necessity of the present."

-- "Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception."

Valdo Spini, a scholar and former member of parliament, says Machiavelli came close but never actually wrote the sentence "the end justifies the means."

That quintessentially cynical concept, Spini says, was attributed to Machiavelli falsely by Antonio Possevino, a Jesuit priest who at the end of the 16th century wrote a satire of Machiavelli's work that tainted the writer's intent.

"I do not think he is a kind of an apologist for dictatorship," Spini says of Machiavelli, "but he understood the deep forces [that] act in society and this is his modernity."

Misrepresented And Misunderstood

Few works of world literature have had so many diverging interpretations, and some of them are projected on a wall of the exhibit.

The philosopher Spinoza was convinced The Prince was a warning to men of what tyrants were capable of; Francis Bacon thought Machiavelli a realist unfettered by Utopian fantasies; Karl Marx considered Machiavelli's work a genuine masterpiece.

Bertrand Russell called The Prince a handbook for gangsters.

The Elizabethan view of Machiavelli as the symbol of evil — Shakespeare's Iago for example — has filtered down to contemporary popular culture.

One display case contains contemporary paraphernalia — buttons, refrigerator magnets, shirts, watches and teddy bears — all emblazoned with the image of Niccolo Machiavelli.

There are Machiavelli handbooks for housewives, for children and for narco-traffickers.

And in the most famous video game in the world, Assassins Creed, the Machiavelli character is not a political thinker but a killer, the head of a sect of assassins.

These items are the latest sign of the enduring impact of a man some scholars describe as — for good or ill — the herald of the modern political era.

But former Italian Prime Minister Giuliano Amato, who wrote an essay for the exhibit catalog, says the Florentine writer has been wrongly described as the bard of cynicism.

"He is misrepresented and misunderstood," Amato wrote. "Because he said politics has to find its own ethics and its own values, disentangling politics from religion and other sets of values."

One of the judgments projected on the exhibition wall is by the great 20th century scholar Isaiah Berlin: Machiavelli, he said, "helped cause men to become aware of the necessity of making agonizing choices between incompatible alternatives in public and private life."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.