It used to be one of the worst places in the world when it came to protecting children.

A 2007 Violence Against Children Survey coordinated by UNICEF and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found one in three girls in Swaziland was sexually abused before age 18. (The global rate is 1 in 5, according to the World Health Organization.)

The next year, the country ranked near the bottom of all African nations for child well-being, a measure that includes legal protections for children and spending on initiatives like education and health care.

But now, Swaziland is being hailed as a shining model of how to protect kids. On July 12, the CDC, WHO and eight other partner groups released a guide to tackling child abuse. Swaziland was singled out as an example of how a government can use a variety of approaches to make major strides.

And a lot of the credit goes to Swaziland's grandmas.

The government wanted to see improvement. So nonprofit groups asked the chiefs who preside over the country's districts: Who could help stand up for children? And the chiefs had a suggestion: grandmothers. They're excellent allies for several reasons, says Rachel Odede, UNICEF's representative in Swaziland. They enjoy respect within the community and often stay home with the community's children.

That was in year 2000. Since then, more than 10,000 grandmothers have enrolled in a new program called "Shoulder to Cry On" to combat child abuse. It's sponsored by government agencies and nonprofit organizations; UNICEF is one of the organizers.

The program has helped address one of the challenges of child abuse — helping children understand that certain kinds of treatment are not OK and should be reported to a grandmother or another trustworthy adult.

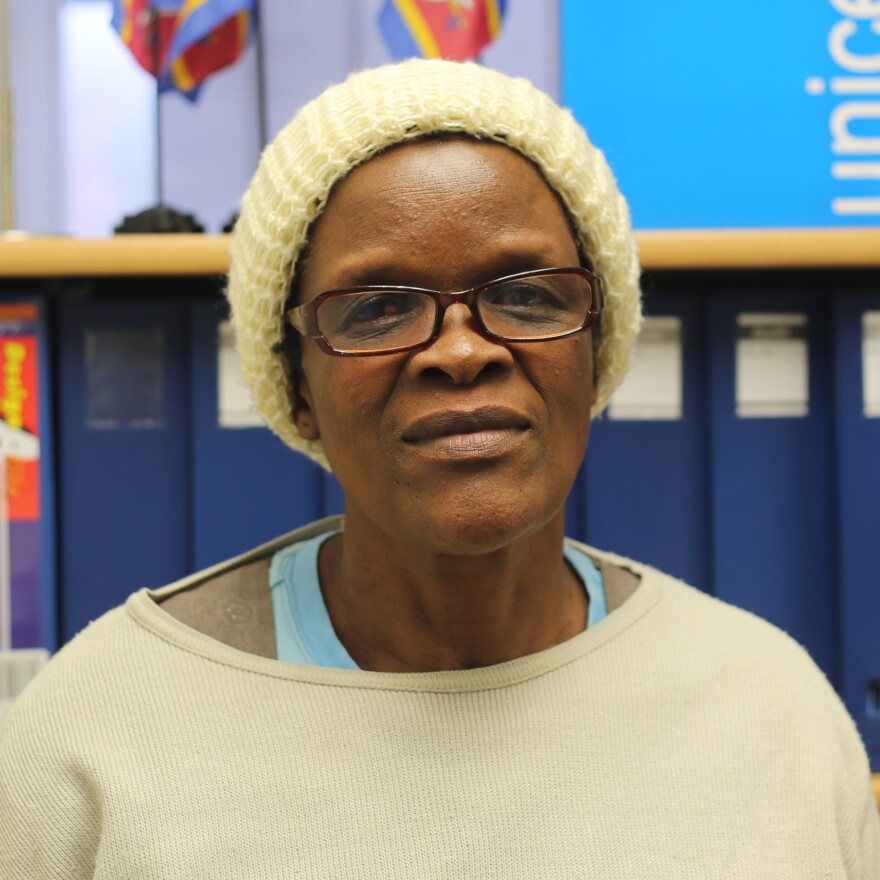

Khanyisile Simelane, a 58-year-old grandmother of eight, was selected at a community meeting to be a shoulder to cry on in 2005. She knocked on doors around the village to explain her new role. Then, she began discussing abuse with children at the community center, where she works as a caregiver.

"I use picture stories mainly," Simelane says. These tales, part of grandmothers' training, are designed to help children identify and report abuse. In the stories, animal behaviors often mimic the actions of abusers; victims can turn to Grandmother Elephant, whose big ears make her a good listener.

"I monitor the children's reactions [to the stories]," says Simelane, "and follow up afterward."

When a child comes to a grandmother to report abuse or the grandmother identifies abuse independently, she takes the child to the region's one-stop center dedicated to abuse victims. There, the child can talk to social workers, receive medical treatment and be interviewed by the police.

Because a lot of abuse occurs at home, Simelane says she faces pushback for exposing inappropriate practices by family members. "This is indeed a difficult job," she admits, adding that some grandmothers have dropped out of the program because of hostile community reaction. "What has sustained me this far is that I'm also a victim of abuse. When I grew up, my parents had separated. I was staying with relatives and was abused as a child. I didn't have anyone to talk to."

Simelane has found that parents may have misconceptions. Some believe that she will teach children to say they're being abused if they're asked to perform household chores. Simelane explains she's targeting sexual and physical abuse, not housework. After she explains this, she says parents usually seem more open to the program.

In addition to enlisting grandmothers, Swaziland's government enacted other initiatives in the wake of the 2007 UNICEF survey. It started a radio campaign to educate people about violence against children and created a database to record incidents of abuse.

By 2013, Swaziland ranked 9th for child well-being among African countries.

CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden credits the Shoulder to Cry On program, as well as the other government initiatives, for Swaziland's rapid improvement. "Grandmothers were a place that kids could turn to," says Frieden, "and there are dozens in every community."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.